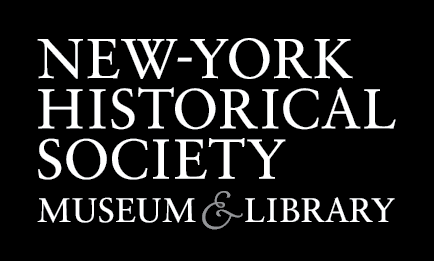

Challenging Jim Crow, 1900–1919

Challenging Jim Crow, 1900–1919

Jim Crow operated freely in America by the turn of the 20th century. Government abandoned the cause of black equality. In white America, the belief in white supremacy and black inferiority deepened.

Increasingly at risk, African Americans looked for ways to survive and advance in a hostile environment. They acted collectively and individually, in art and politics and everyday life. And they shouldered the responsibilities of citizenship, even fighting in America’s wars, though the essential rights of citizens were denied them. Their determined efforts produced new leaders, and organizations that demanded racial justice.

The Lost Cause

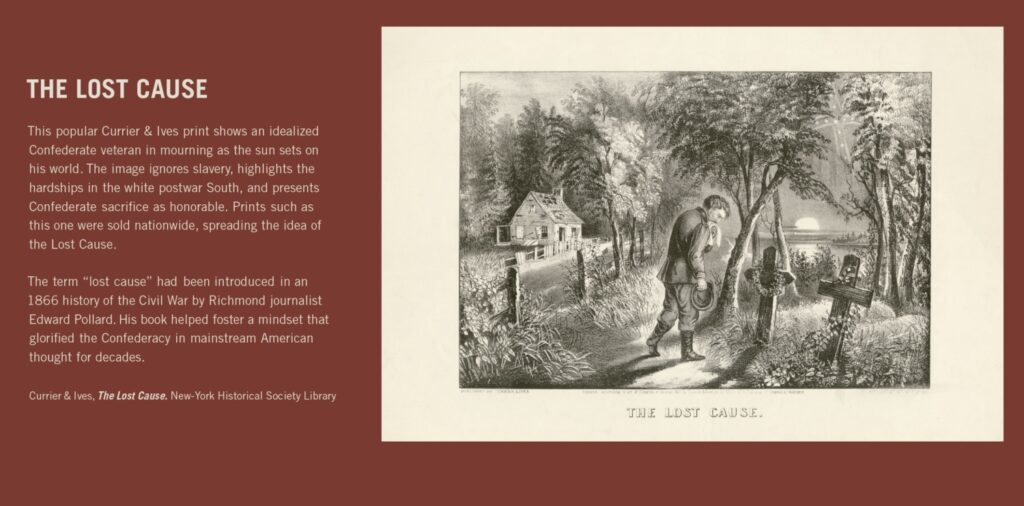

White Americans, North and South, adopted a version of the past that rewrote Civil War and Reconstruction history. According to the “Lost Cause” ideology, slavery was benign, the Civil War was fought over states’ rights, not slavery, and the Confederacy was an honorable endeavor. Reconstruction was deemed a failure. It was thought of as a time of “Negro rule” when African Americans had proved incapable of properly exercising their political rights.

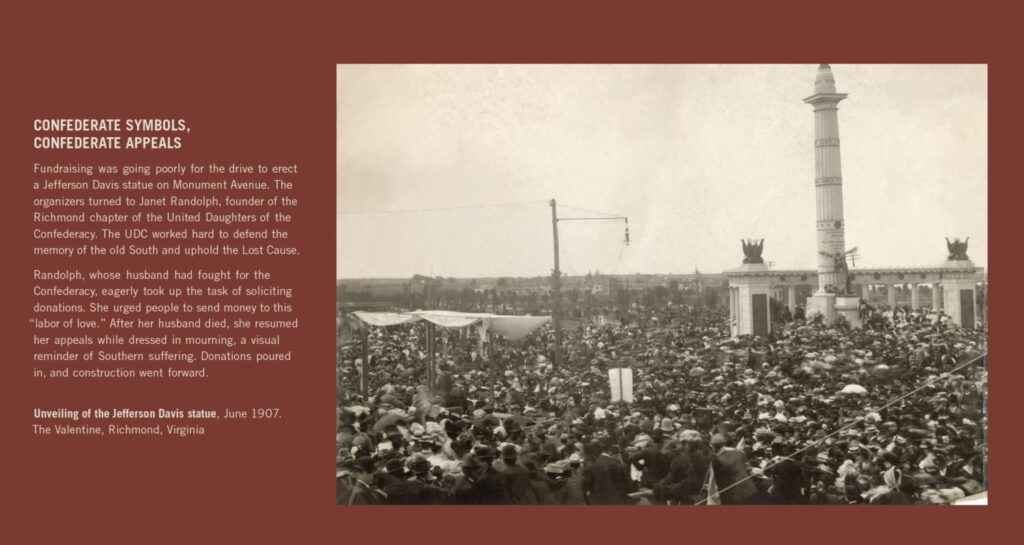

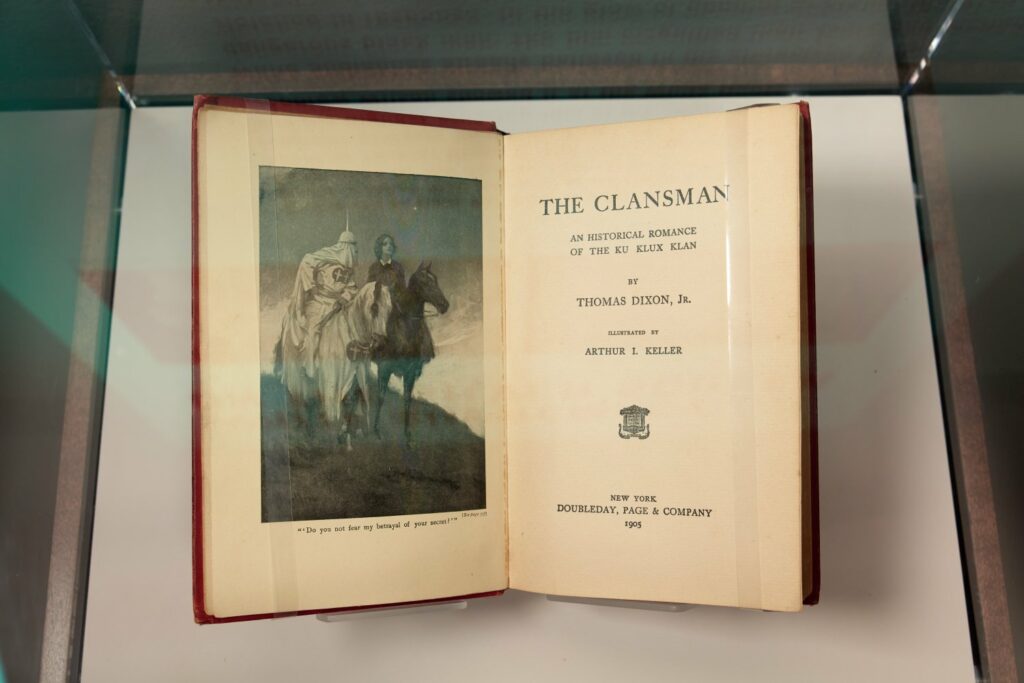

Historians wrote books that promulgated the Lost Cause. Artists and writers created works that hailed the Confederacy and romanticized plantation life. Scientists explained racial hierarchy by claiming that the white race was biologically superior and non-whites were more susceptible to criminality. President Woodrow Wilson’s administration segregated the federal workforce. Throughout the South, monuments were erected in honor of the Confederacy and white supremacy. The Ku Klux Klan reemerged.

White Supremacy on the Silver Screen

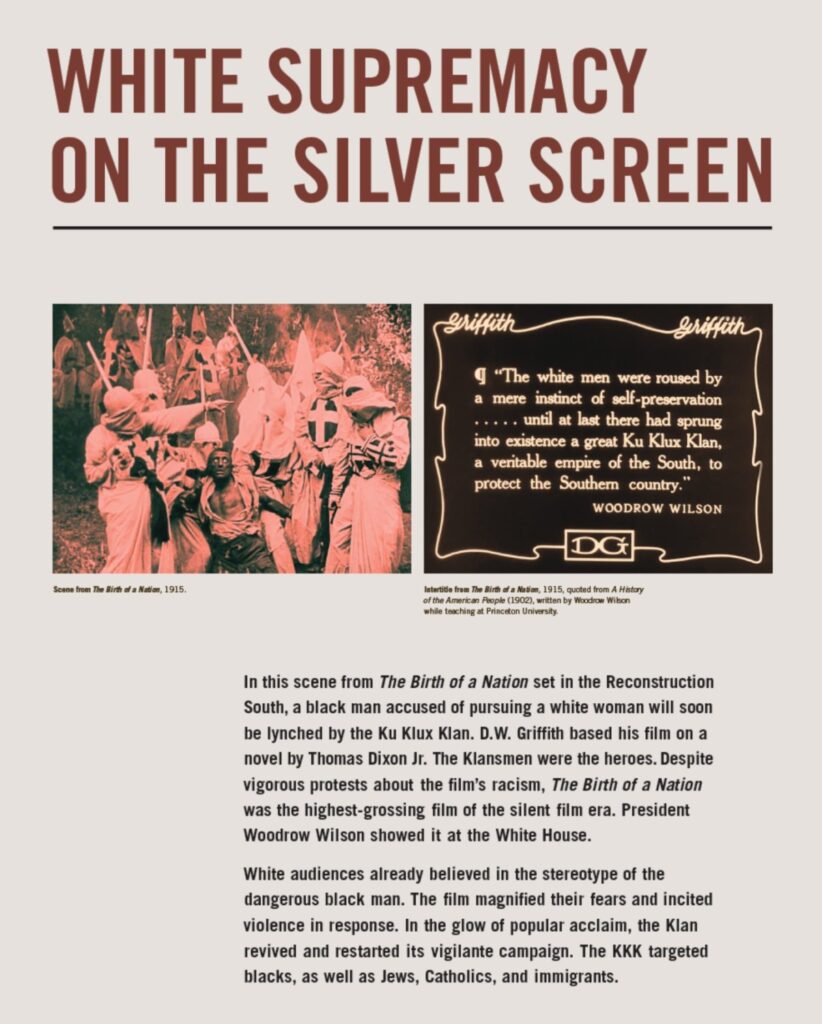

In this scene from The Birth of a Nation set in the Reconstruction South, a black man accused of pursuing a white woman will soon be lynched by the Ku Klux Klan. D.W. Griffith based his film on a novel by Thomas Dixon Jr. The Klansmen were the heroes. Despite vigorous protests about the film’s racism, The Birth of a Nation was the highest-grossing film of the silent film era. President Woodrow Wilson showed it at the White House.

White audiences already believed in the stereotype of the dangerous black man. The film magnified their fears and incited violence in response. In the glow of popular acclaim, the Klan revived and restarted its vigilante campaign. The KKK targeted blacks, as well as Jews, Catholics, and immigrants.

Black Resistance

From the start, African Americans resisted Jim Crow, even as they struggled to stay safe. Their actions took many forms, large and small. Some started businesses to serve unmet needs in black communities. Others produced art and writings that reflected on the black experience. New organizations mounted legal challenges to the infrastructure of Jim Crow. And tens of thousands of African Americans took the step of leaving the South behind for the North and West.

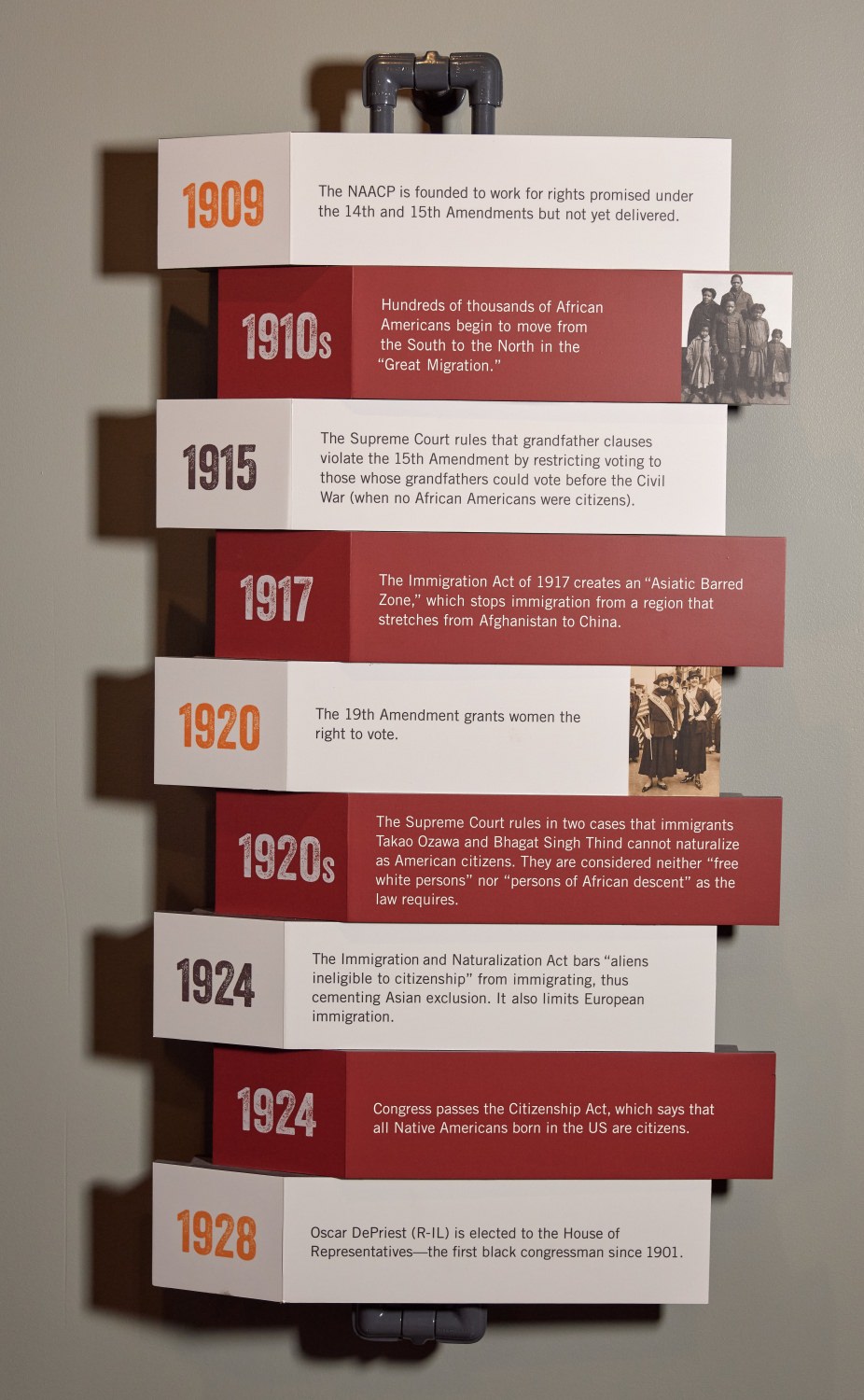

The turn of the twentieth century brought new leaders and organizations to the fore. Groups such as the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and the Urban League mounted national campaigns for equality and against discrimination and violence. One massive effort protested the blockbuster film The Birth of a Nation, which praised the Ku Klux Klan and denigrated blacks.

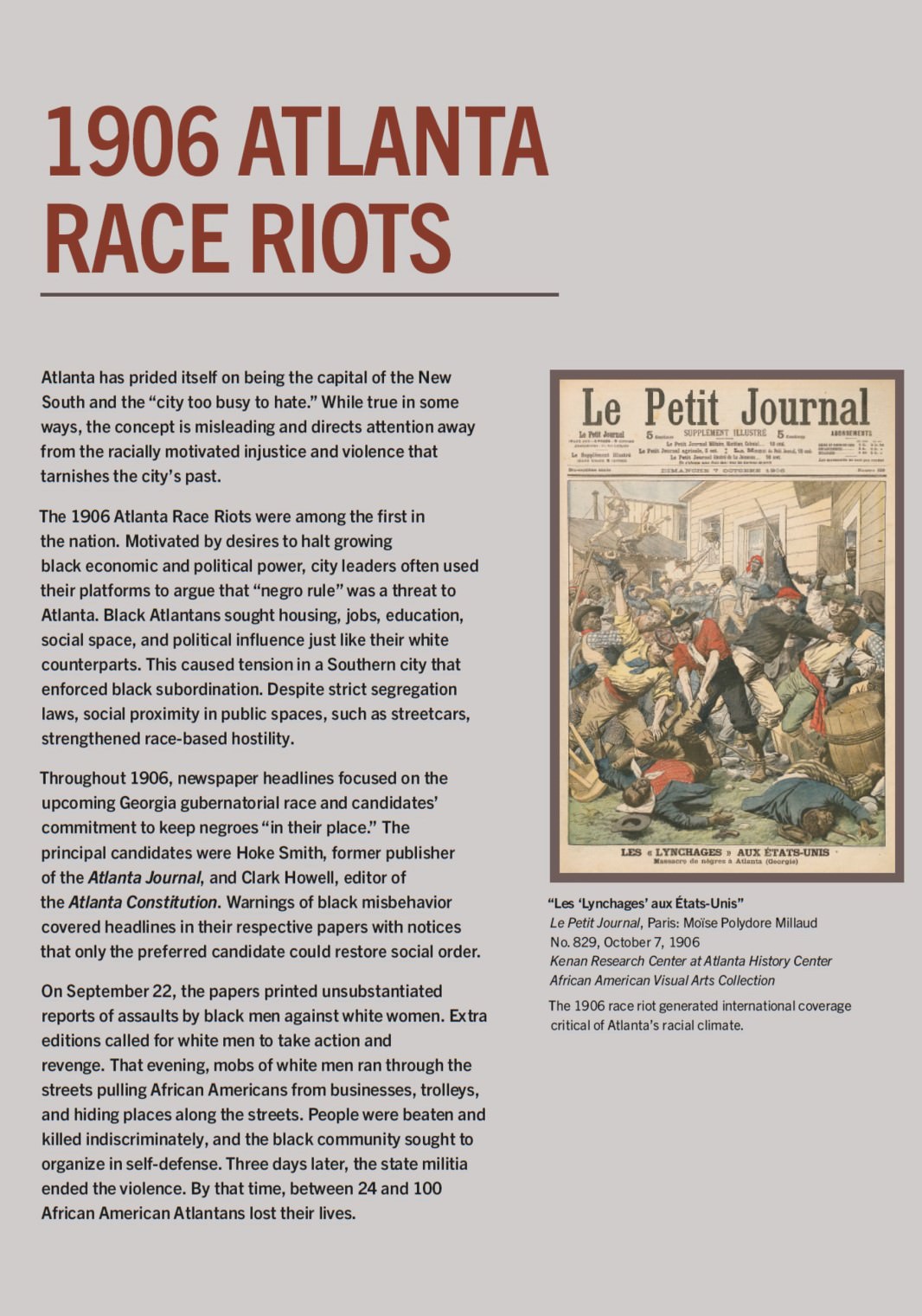

1906 Atlanta Race Riots

Atlanta has prided itself on being the capital of the New South and the “city too busy to hate.” While true in some ways, the concept is misleading and directs attention away from the racially motivated injustice and violence that tarnishes the city’s past.

The 1906 Atlanta Race Riots were among the first in the nation. Motivated by desires to halt growing black economic and political power, city leaders often used their platforms to argue that “negro rule” was a threat to Atlanta. Black Atlantans sought housing, jobs, education, social space, and political influence just like their white counterparts. This caused tension in a Southern city that enforced black subordination. Despite strict segregation laws, social proximity in public spaces, such as streetcars, strengthened race-based hostility.

Throughout 1906, newspaper headlines focused on the upcoming Georgia gubernatorial race and candidates’ commitment to keep negroes “in their place.” The principal candidates were Hoke Smith, former publisher of the Atlanta Journal, and Clark Howell, editor of the Atlanta Constitution. Warnings of black misbehavior covered headlines in their respective papers with notices that only the preferred candidate could restore social order.

On September 22, the papers printed unsubstantiated reports of assaults by black men against white women. Extra editions called for white men to take action and revenge. That evening, mobs of white men ran through the streets pulling African Americans from businesses, trolleys, and hiding places along the streets. People were beaten and killed indiscriminately, and the black community sought to organize in self-defense. Three days later, the state militia ended the violence. By that time, between 24 and 200 African American Atlantans lost their lives.

CONFRONT

W.E.B. Du Bois

Beginnings: 1900

William Edward Burghardt Du Bois went to the international exposition in Paris in 1900 to showcase African American achievements. He was 32, the first black man to earn a Harvard doctorate, and a respected, trailblazing scholar. His “Exhibit of American Negroes” displayed dozens of statistical charts and more than 350 photos. Du Bois hoped that evidence of black progress would counter racist claims of black inferiority. His exhibit won a gold medal.

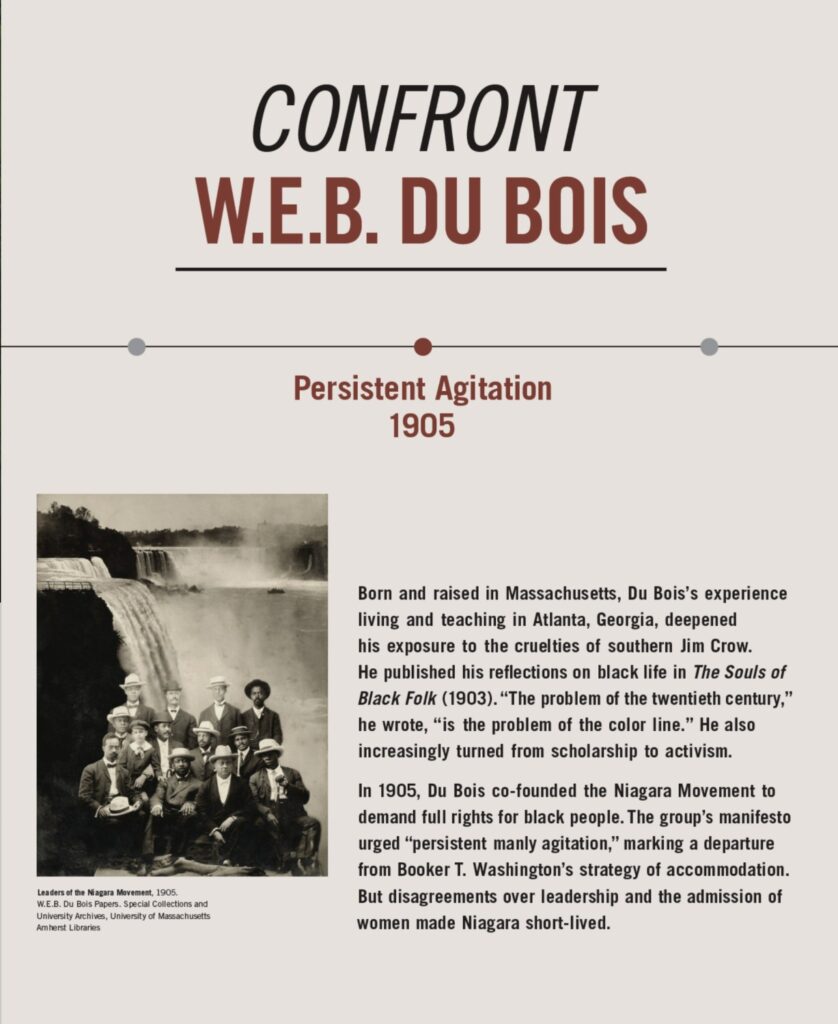

Persistent Agitation: 1905

Born and raised in Massachusetts, Du Bois’s experience living and teaching in Atlanta, Georgia, deepened his exposure to the cruelties of southern Jim Crow. He published his reflections on black life in The Souls of Black Folk (1903). “The problem of the twentieth century,” he wrote, “is the problem of the color line.” He also increasingly turned from scholarship to activism.

In 1905, Du Bois co-founded the Niagara Movement to demand full rights for black people. The group’s manifesto urged “persistent manly agitation,” marking a departure from Booker T. Washington’s strategy of accommodation. But disagreements over leadership and the admission of women made Niagara short-lived.

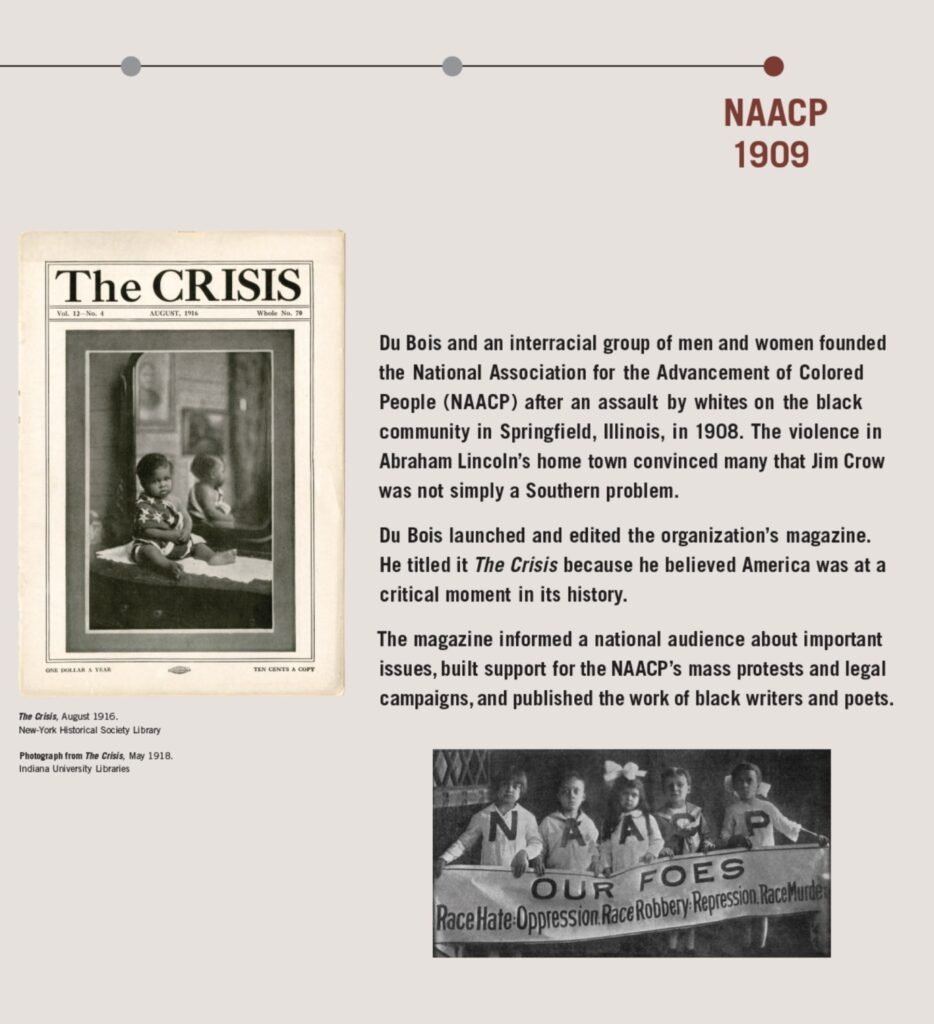

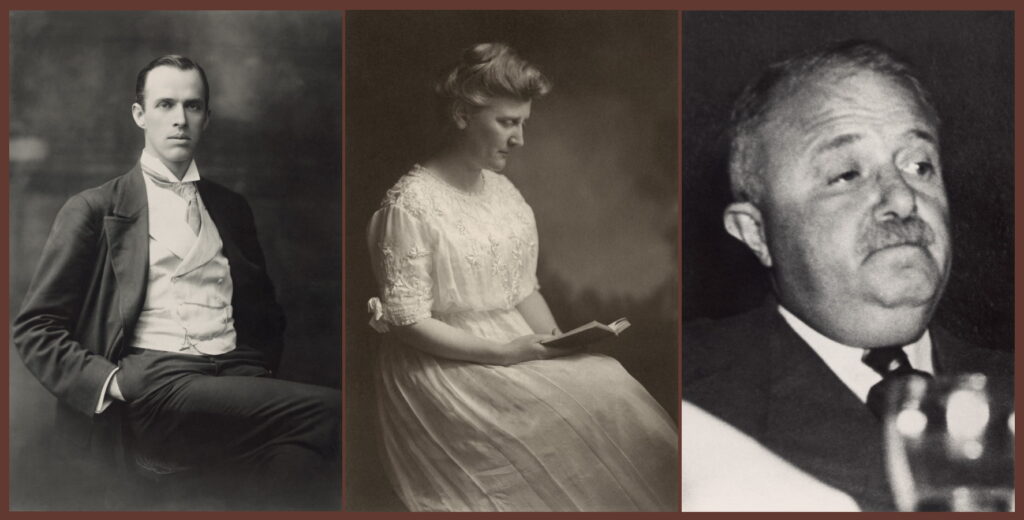

NAACP: 1909

Du Bois and an interracial group of men and women founded the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) after an assault by whites on the black community in Springfield, Illinois, in 1908. The violence in Abraham Lincoln’s home town convinced many that Jim Crow was not simply a Southern problem.

Du Bois launched and edited the organization’s magazine. He titled it The Crisis because he believed America was at a critical moment in its history.

The magazine informed a national audience about important issues, built support for the NAACP’s mass protests and legal campaigns, and published the work of black writers and poets.

INNOVATE

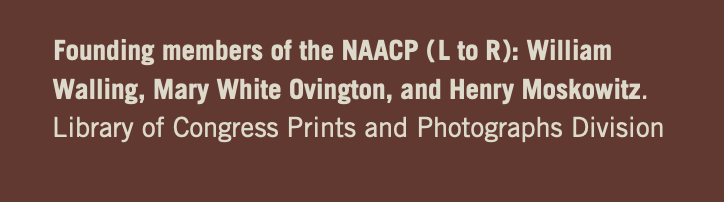

Maggie Walker

As a teenager, Maggie Walker joined the Independent Order of St. Luke, a national association of African Americans based in Richmond, Virginia. She was named its leader in her early 30s and dramatically expanded the group’s membership.

This gifted entrepreneur created businesses to help Richmond’s black community advance economically. When she started the St. Luke’s Penny Savings Bank, she became the first black female bank president in the US. Other St. Luke’s enterprises included a newspaper, an insurance company, a clothing factory, and a store. All hired black workers, especially young women who otherwise had few job opportunities. Black consumers could now shop and conduct daily tasks safe from the abuses of Jim Crow.

In 2017, a statue of Maggie Walker was erected in Richmond, a few blocks from the city’s Confederate monuments.

For more information, visit www.nps.gov/mawa

CREATE

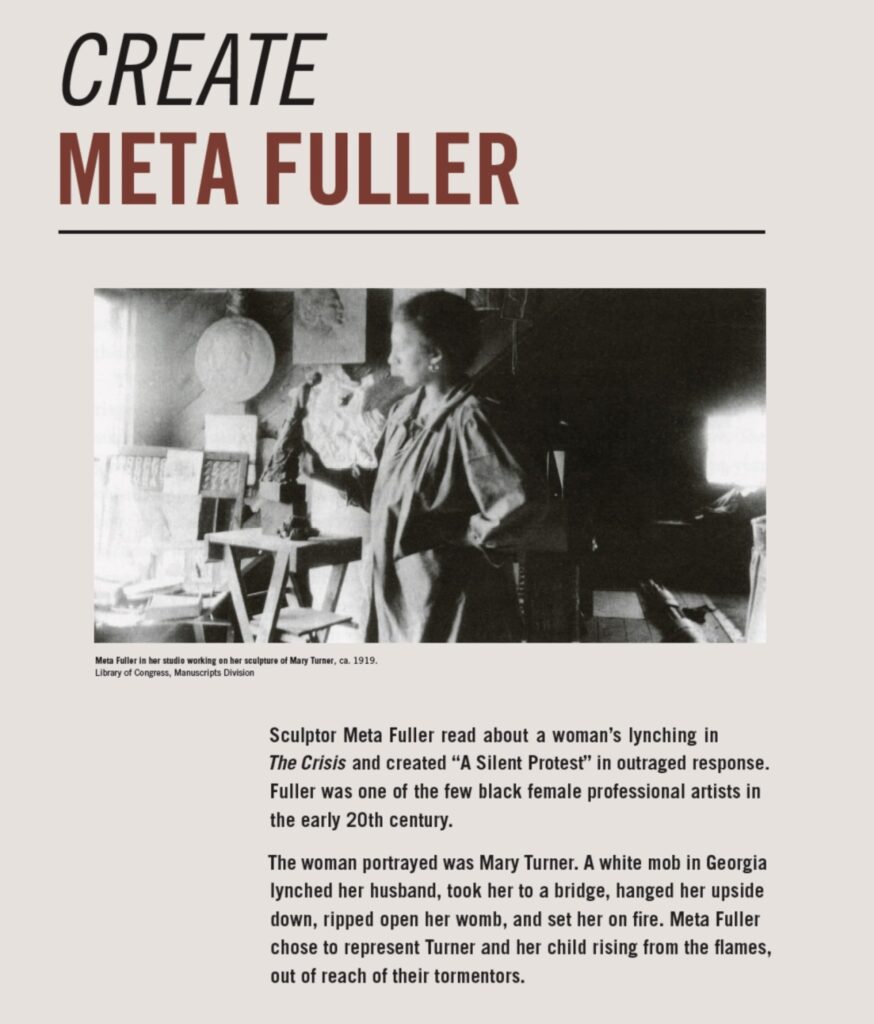

Meta Fuller

Sculptor Meta Fuller read about a woman’s lynching in The Crisis and created “A Silent Protest” in outraged response. Fuller was one of the few black female professional artists in the early 20th century.

The woman portrayed was Mary Turner. A white mob in Georgia lynched her husband, took her to a bridge, hanged her upside down, ripped open her womb, and set her on fire. Meta Fuller chose to represent Turner and her child rising from the flames, out of reach of their tormentors.

LEAVE

The Great Migration

Pullman porters worked in railroad sleeping cars, making the mostly white passengers comfortable. Porters traveled much of the country and told friends and relatives in the Jim Crow South that life was better in the North. As evidence, they brought back copies of African American newspapers like the Chicago Defender. The North looked like the promised land to many.

Black Southerners began moving north in large numbers in the 1910s, mostly heading to cities, especially New York, Chicago, and Detroit. Factory jobs beckoned, especially after World War I cut off immigration from Europe.

Southern white employers tried to stop them from leaving, and northern white workers treated them as competitors, but African Americans continued to flee the South. Their exodus became known as the Great Migration.

HARLEM

Building Harlem

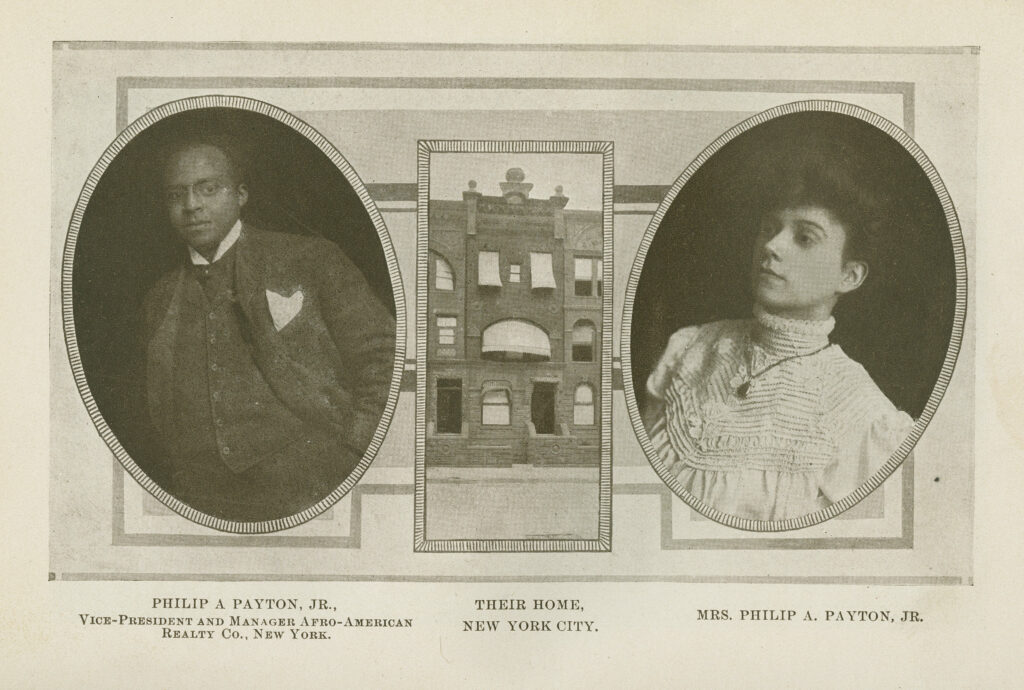

The advent of black Harlem was no accident. It was engineered in part by African American entrepreneur Philip Payton, especially after race riots in midtown in the early 1900s left black residents feeling endangered, and wishing for a safe enclave in New York City.

Payton was already working in real estate in Harlem when a white company evicted its black tenants to stop blacks from relocating to the neighborhood. Payton made his move. He bought the neighboring two buildings, evicted their white residents, and allowed the recently ejected black tenants to move in. Payton’s Afro-American Realty Company continued to buy buildings and rent to black tenants. Booker T. Washington congratulated him on having “turned the tables on those who desired to injure the race.”

Harlem’s black population swelled with the influx of migrants from the South and from the Caribbean. By 1920, Harlem would become the largest black urban community in the country.

Philip A. Payton, Jr., Mrs. Philip A. Payton, Jr., and Their Home, 1907. Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, New York Public Library

White Rose Mission

262 W. 136th Street

Victoria Earle Matthews founded the White Rose Mission in 1897 to help newly arrived black migrant women find housing and decent work. Originally located on the Upper East Side, the White Rose moved to Harlem in 1918. It offered classes, child care, temporary housing, and other services to help vulnerable people through a difficult time in an unfamiliar city.

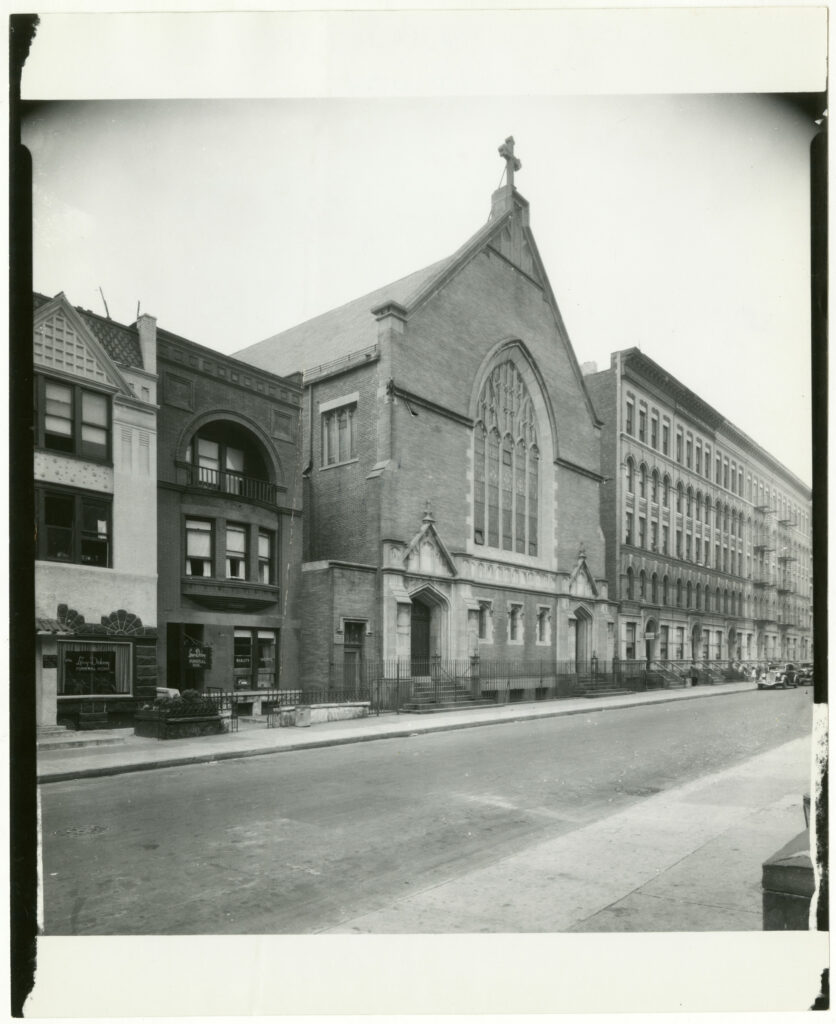

St. Philip’s Church

210 W. 134th Street

St. Philip’s Episcopal Church, founded in 1809, is one of the country’s oldest black parishes. From its origins in lower Manhattan, the church moved uptown several times, following the black community and seeking safety from sporadic violence such as the race riot of 1900.

Around the turn of the century, church rector Hutchens Chew Bishop began buying Harlem rental properties, evicting whites and renting to blacks. With the income, he bought land on 134th Street and hired black architect Vertner Tandy to design a new building. The impressive Gothic structure provided a spiritual and community home for black parishioners in Harlem.

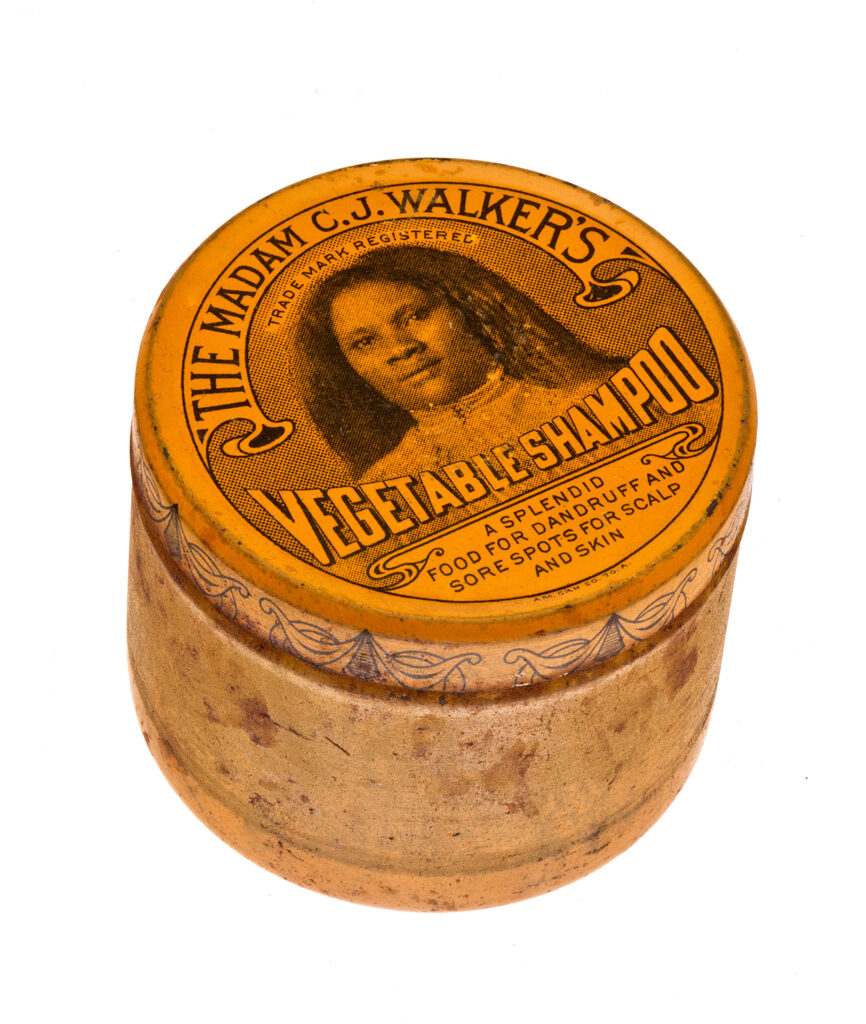

Madam C.J. Walker

108 W. 136th Street

Madam C.J. Walker built an empire from cosmetics. She began her own line of hair and skin products and popularized methods of caring for and styling black hair. Her success took her from Indianapolis to New York City.

Walker’s brownstone house in Harlem was a center of black social life. It also housed a school and beauty parlor where she trained black women to open their own salons, stocked with her products. Walker became a millionaire, and her students gained a solid foothold in Harlem’s growing economy.

Speaker’s Corner

135th and Lenox

Many Caribbean immigrants landed in Harlem, but only one was known as the Black Socrates. Crowds gathered when the charismatic socialist Hubert Harrison took to his street corner and railed against oppression. He called it his “outdoor university.” Harrison criticized Booker T. Washington’s accommodationist approach, and encouraged militant resistance to white mobs.

As Harlem became a center of black America’s fight against white racism, crowds continued to flock to Speaker’s Corner to hear Harrison and others share their views on political issues.

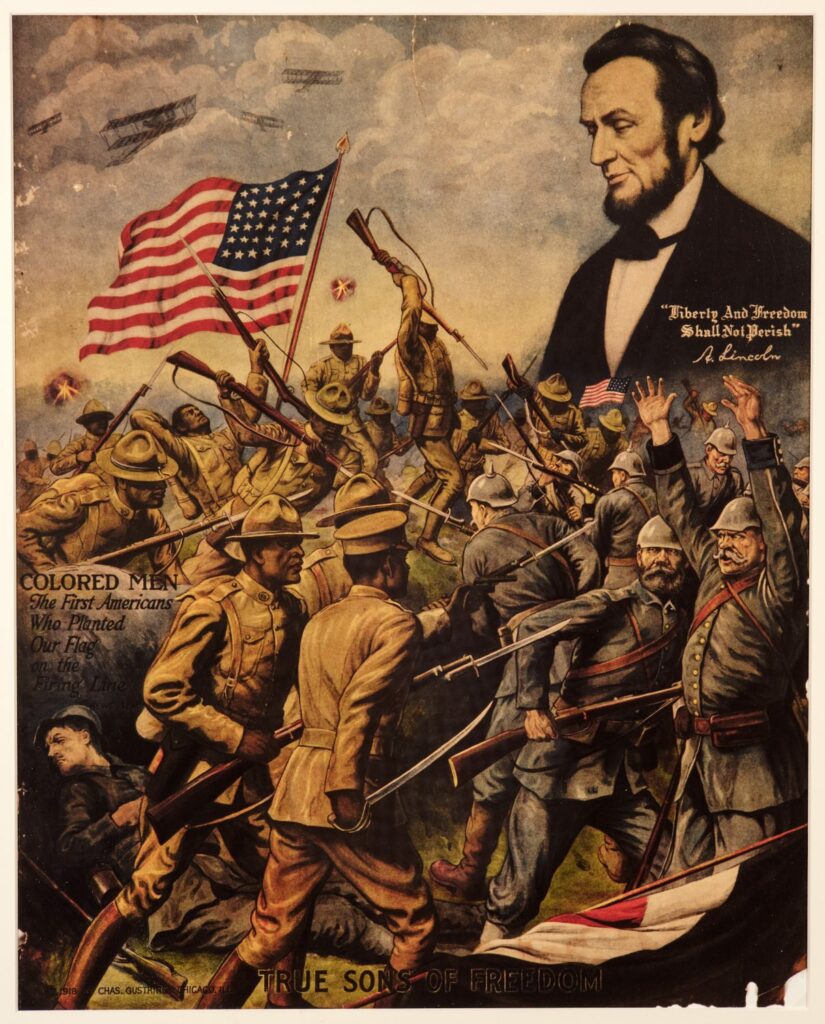

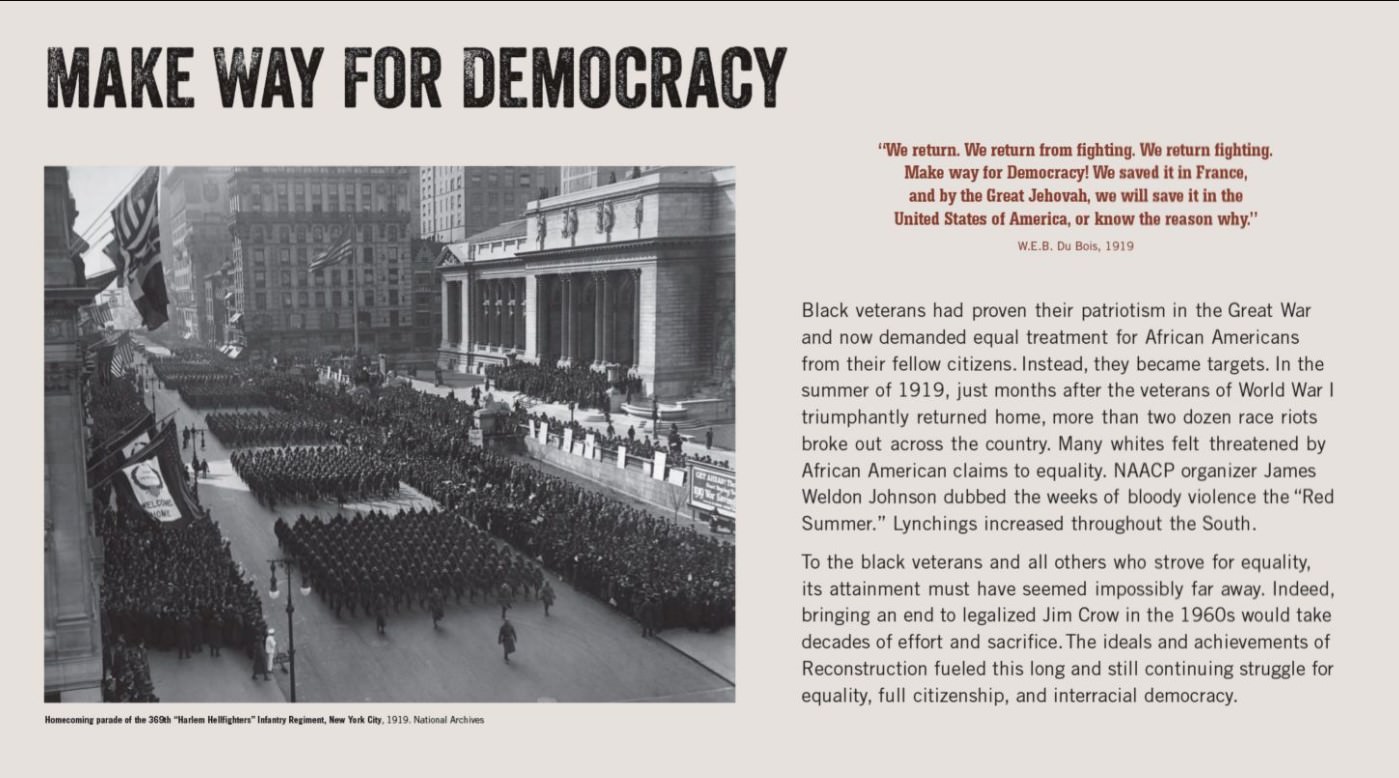

Black Fighters in World War I

Henry Johnson volunteered for the army and was sent to France in WWI. His unit, the 369th Infantry Regiment of the 93rd Division, served under French command and spent more time in continuous combat than any other American unit. They were known as the Harlem Hellfighters. Johnson was awarded France’s highest military honor for repelling a German attack and was viewed as a war hero at home.

Henry Johnson’s story was not typical. Close to 400,000 African Americans served in the war, but most had been drafted. Moreover, few saw combat because white officers believed blacks were better suited to manual labor. The example set by the Harlem Hellfighters, and Henry Johnson himself, directly challenged those prejudices.

African American women advanced the war effort by working as nurses, ambulance drivers, and munitions workers. They also raised funds for relief organizations and other needs.

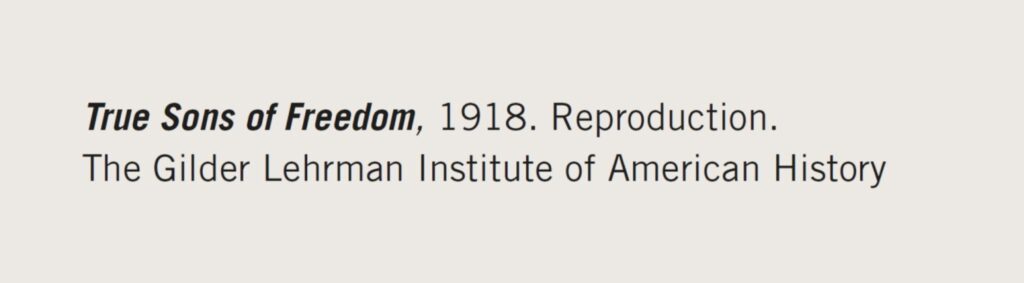

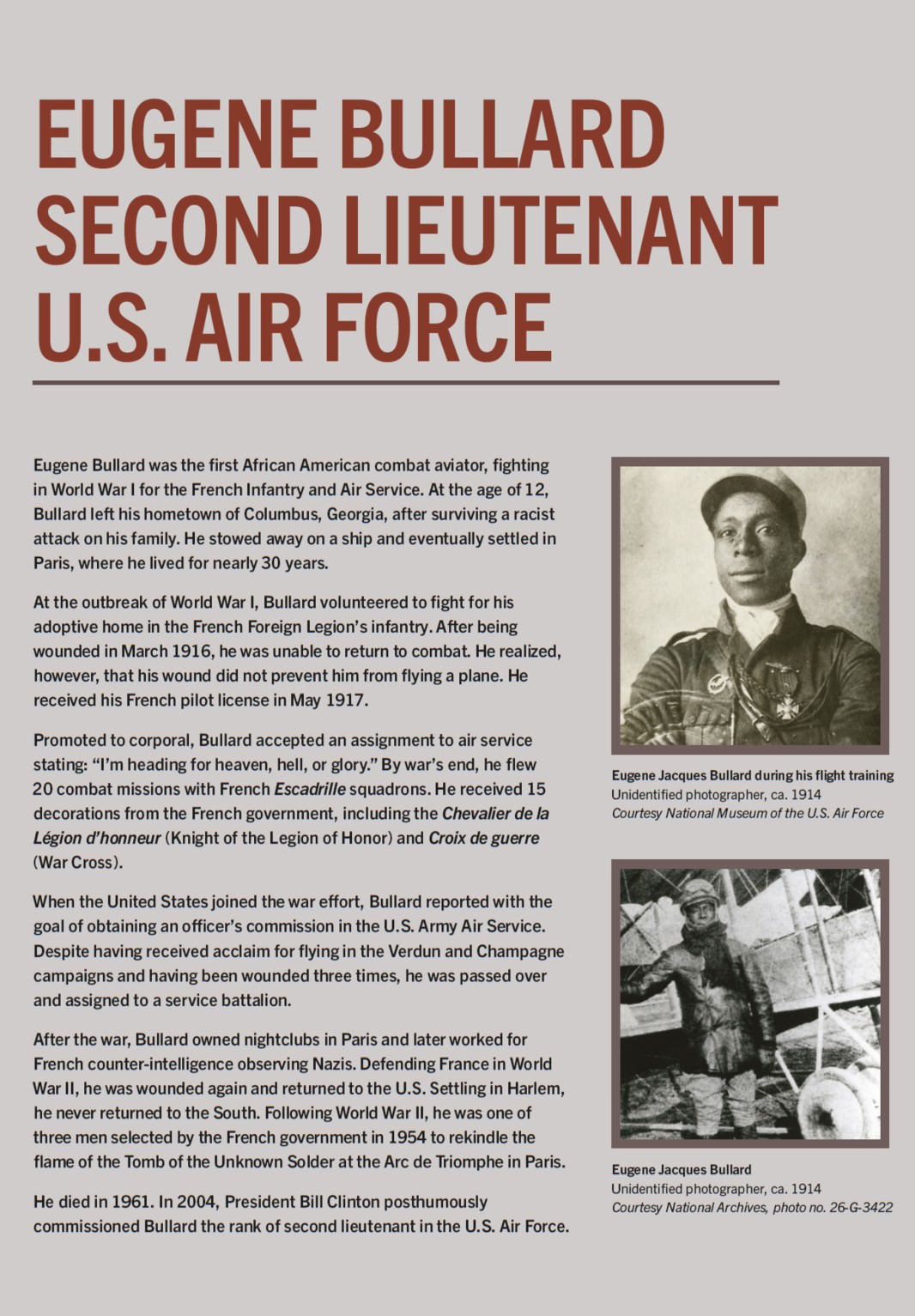

Eugene Bullard, Second Lieutenant, U.S. Air Force

Eugene Bullard was the first African American combat aviator, fighting in World War I for the French Infantry and Air Service. At the age of 12, Bullard left his hometown of Columbus, Georgia, after surviving a racist attack on his family. He stowed away on a ship and eventually settled in Paris, where he lived for nearly 30 years.

At the outbreak of World War I, Bullard volunteered to fight for his adoptive home in the French Foreign Legion’s infantry. After being wounded in March 1916, he was unable to return to combat. He realized, however, that his wound did not prevent him from flying a plane. He received his French pilot license in May 1917.

Promoted to corporal, Bullard accepted an assignment to air service stating: “I’m heading for heaven, hell, or glory.” By war’s end, he flew 20 combat missions from French Escadrille squadrons. He received 15 decorations from the French government, including the Chevalier de la Légion d’honneur (Knight of the Legion of Honor) and Croix de guerre (War Cross).

When the United States joined the war effort, Bullard reported with the goal of obtaining and officer’s commission in the U.S. Army Air Service. Despite having received acclaim for flying in the Verdun and Champagne campaigns and having been wounded three times, he was passed over and assigned to a service battalion.

After the war, Bullard owned nightclubs in Paris and later worked for French counter-intelligence observing Nazis. Defending France in World War II, he was wounded again and returned to the U.S. Settling in Harlem, he never returned to the South. Following World War II, he was one of three men selected by the French government in 1954 to rekindle the flame of the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier at the Arc de Triomphe in Paris.

He died in 1961. In 2004, President Bill Clinton posthumously commissioned Bullard the rank of second lieutenant in the U.S. Air Force.

Make Way for Democracy

“We return. We return from fighting. We return fighting. Make way for Democracy! We saved it in France, and by the Great Jehovah, we will save it in the United States of America, or know the reason why.”

–W.E.B. Du Bois, 1919

Black veterans had proven their patriotism in the Great War and now demanded equal treatment for African Americans from their fellow citizens. Instead, they became targets. In the summer of 1919, just months after the veterans of World War I triumphantly returned home, more than two dozen race riots broke out across the country. Many whites felt threatened by African American claims to equality. NAACP organizer James Weldon Johnson dubbed the weeks of bloody violence the “Red Summer.” Lynchings increased throughout the South.

To the black veterans and all others who strove for equality, its attainment must have seemed impossibly far away. Indeed, bringing an end to legalized Jim Crow in the 1960s would take decades of effort and sacrifice. The ideals and achievements of Reconstruction fueled this long and still continuing struggle for equality, full citizenship, and interracial democracy.