Reconstructing Citizenship, 1865–1877

Reconstructing Citizenship, 1865–1877

Reconstruction began with the Confederate surrender that ended the Civil War. America needed to reunite, heal, and change. Just at this crucial moment, a Southern sympathizer killed President Lincoln. Vice President Andrew Johnson took over.

A burning question faced the nation during Reconstruction. Would black people now be accepted as equals? The country was deeply divided. Some envisioned a radically new interracial democracy. Others wanted the old America, with strict racial lines intact and whites in control. President Johnson agreed with the latter. He brought his support for white supremacy to the helm of government. An urgent contest for power erupted in Washington and throughout the country.

The struggle for black freedom and equality during Reconstruction produced long strides forward and bruising setbacks. Promises were both made and betrayed. But those twelve years changed the meaning of citizenship fundamentally, for black people and for all Americans.

Why was it called Reconstruction?

During the Civil War, President Lincoln had looked forward to a time when the nation would undergo a process of “reconstruction.” The term is used to define the period of national rebuilding and transformative change following the Civil War.

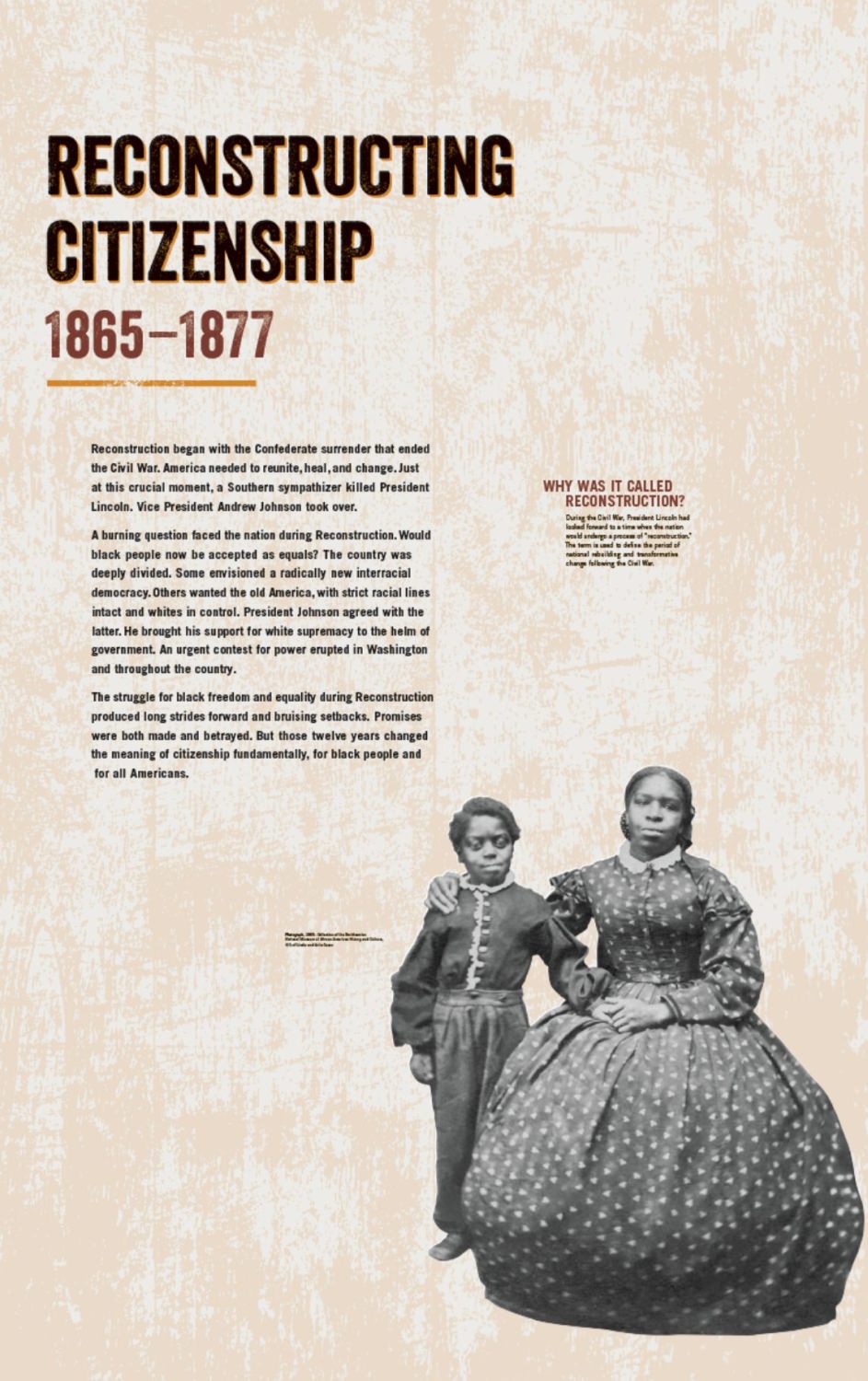

Congress vs. The President

The Republican Party of Lincoln controlled Congress at the end of the war. But southern Democrat Andrew Johnson was now president. As Reconstruction began in 1865, the two parties clashed repeatedly.

Republicans sought to create opportunity for African Americans. They also tried to prevent Confederate leaders from regaining political power and again threatening national unity. The president’s opposition made Congress act more forcefully.

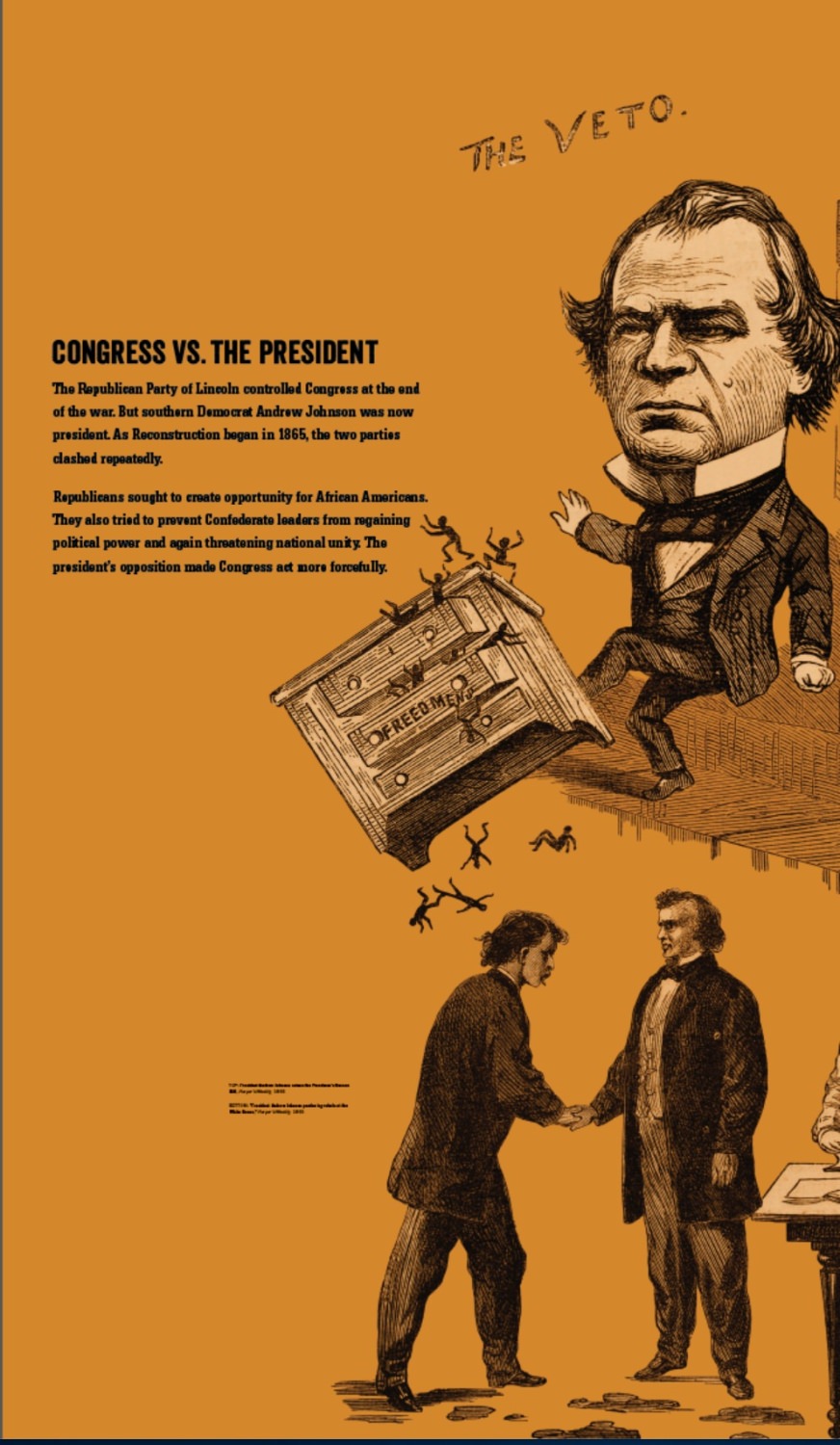

Expanding Equal Rights

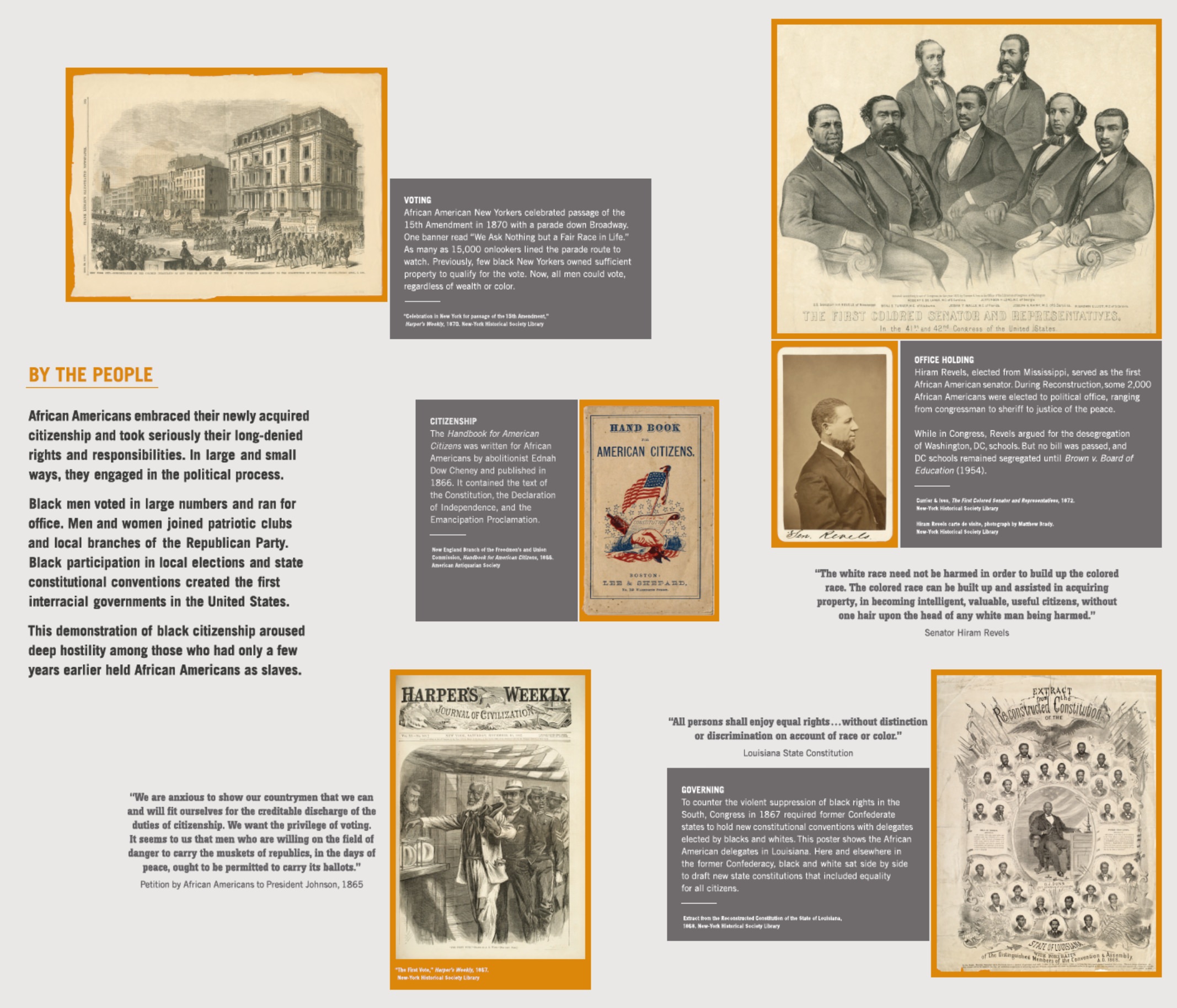

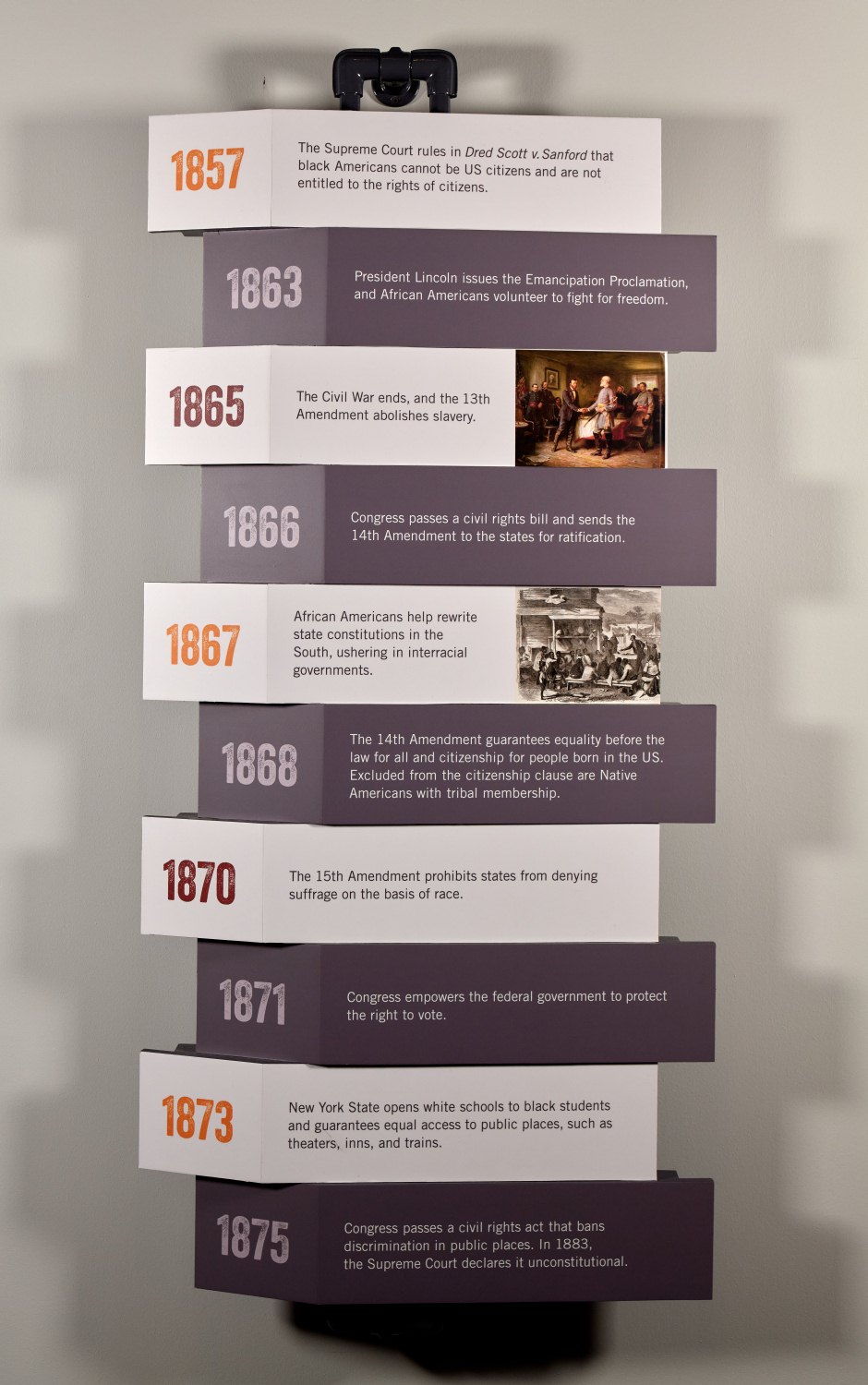

In 1866, Republicans in Congress made history. Infuriated by the South’s repressive state laws concerning blacks, they passed a civil rights bill over President Johnson’s veto. They also asked the states to ratify the 14th Amendment to the Constitution.

Both measures secured equality before the law and citizenship for African Americans and all those born in the US.

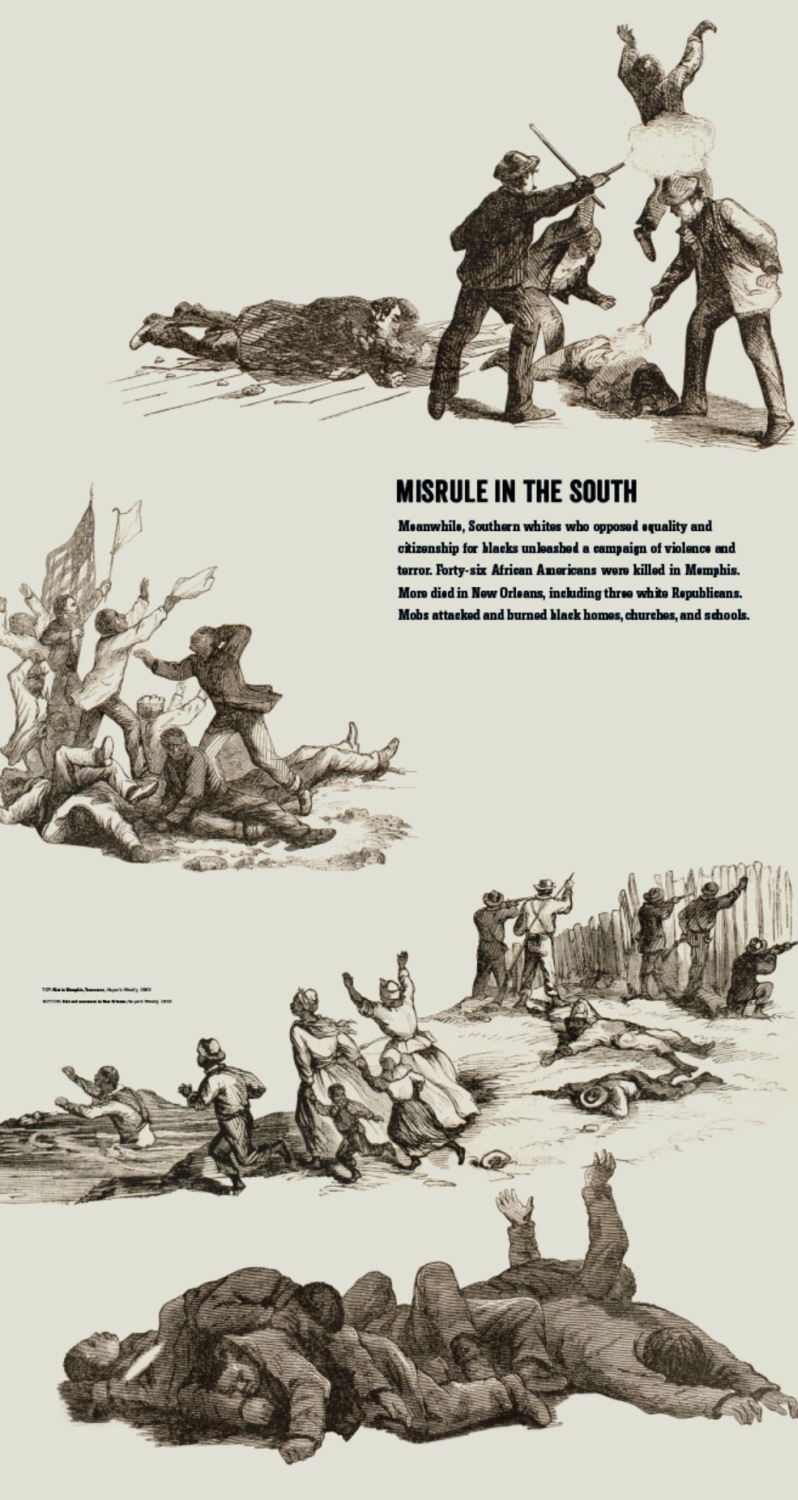

Misrule in the South

Meanwhile, Southern whites who opposed equality and citizenship for blacks unleashed a campaign of violence and terror. Forty-six African Americans were killed in Memphis. More died in New Orleans, including three white Republicans. Mobs attacked and burned black homes, churches, and schools.

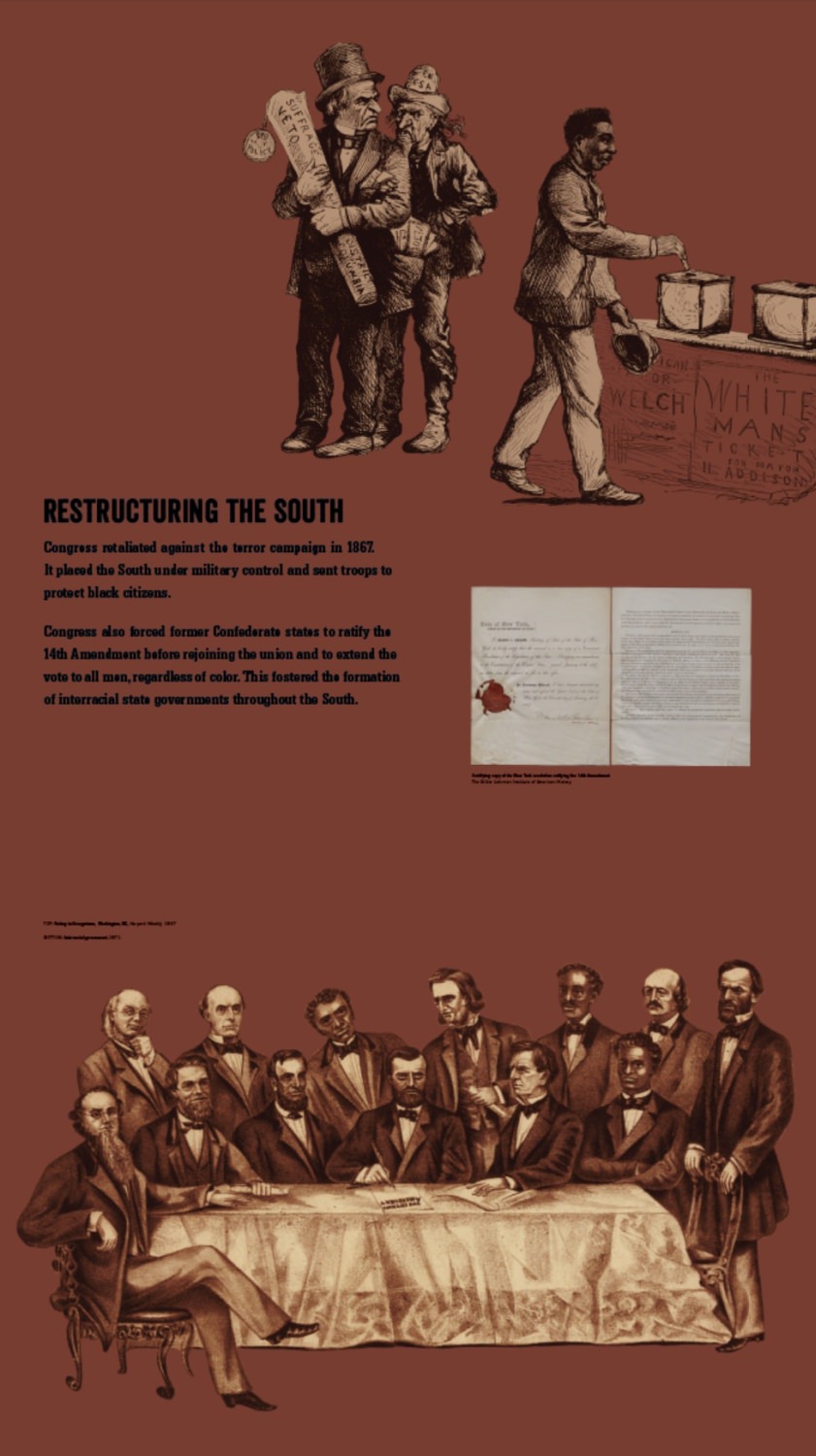

Restructuring the South

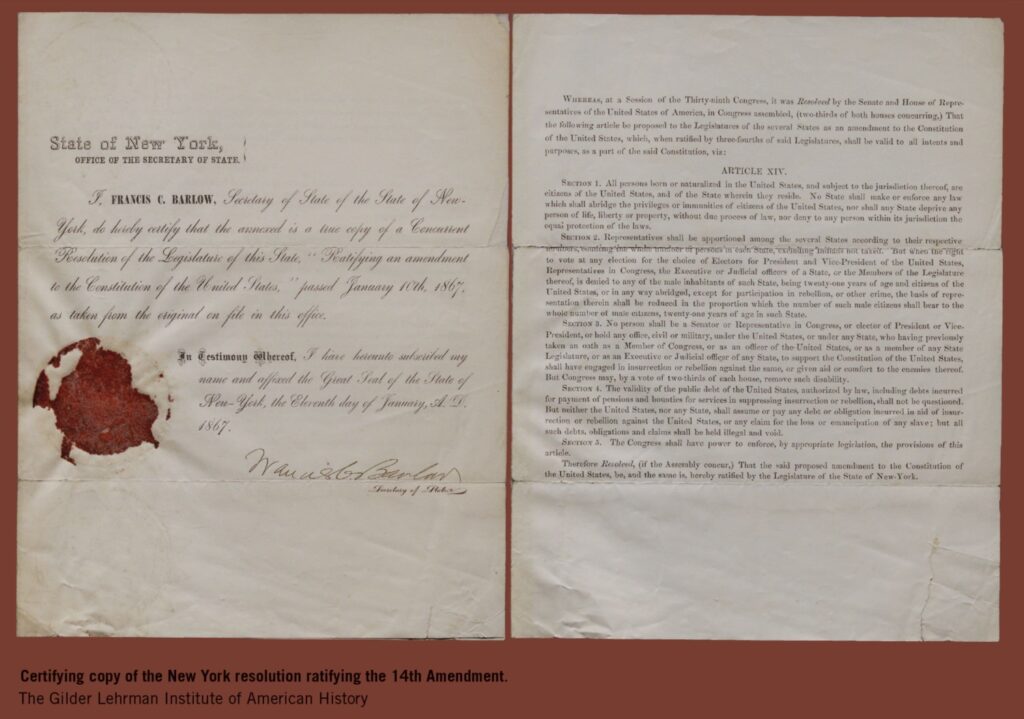

Congress retaliated against the terror campaign in 1867. It placed the South under military control and sent troops to protect black citizens.

Congress also forced former Confederate states to ratify the 14th Amendment before rejoining the union and to extend the vote to all men, regardless of color. This fostered the formation of interracial state governments throughout the South.

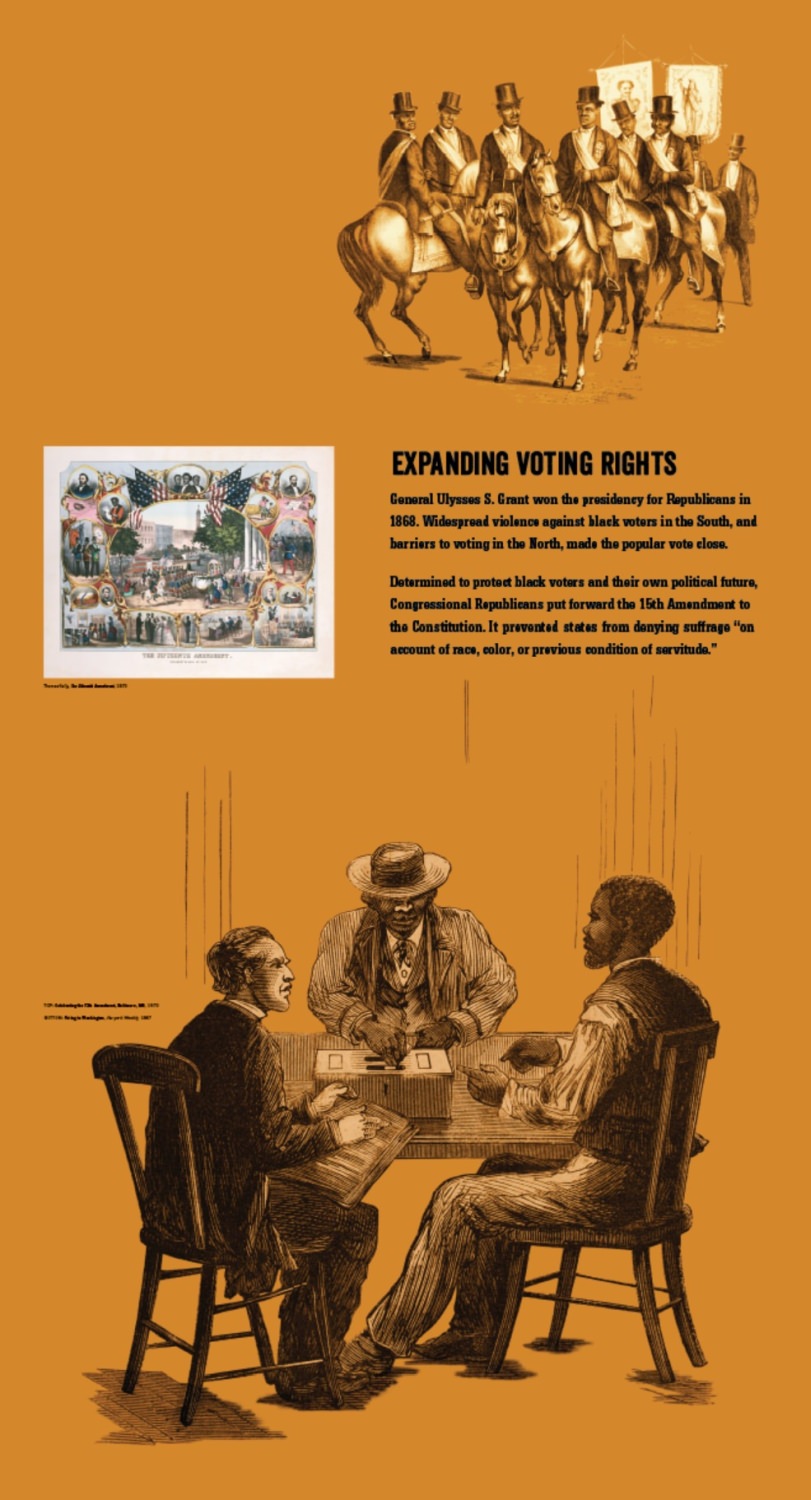

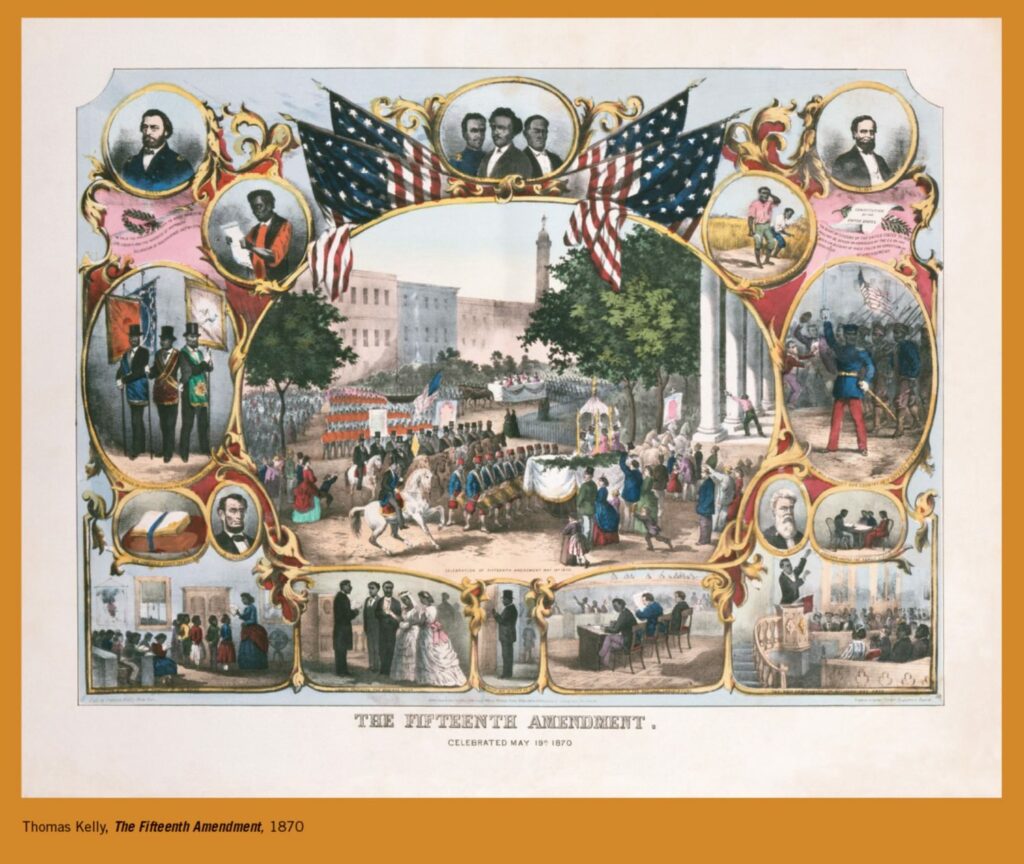

Expanding Voting Rights

General Ulysses S. Grant won the presidency for Republicans in 1868. Widespread violence against black voters in the South, and barriers to voting in the North, made the popular vote close.

Determined to protect black voters and their own political future, Congressional Republicans put forward the 15th Amendment to the Constitution. It prevented states from denying suffrage “on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.”

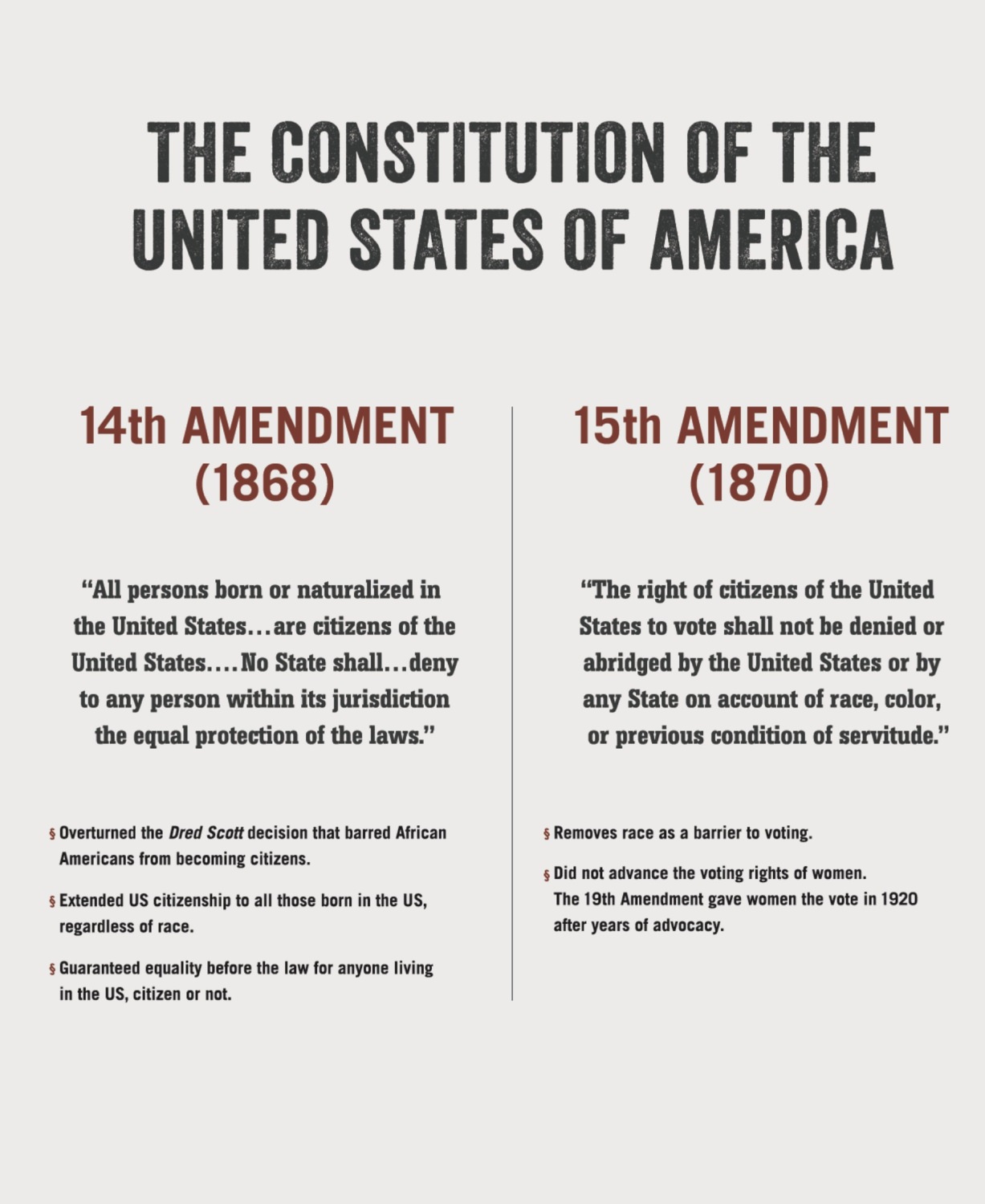

The Constitution of the United States of America

14th Amendment (1868)

“All persons born or naturalized in the United States . . . are citizens of the United States. . . . No State shall . . . deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.”

- Overturned the Dred Scott decision that barred African Americans from becoming citizens.

- Extended US citizenship to all those born in the US, regardless of race.

- Guaranteed equality before the law for anyone living in the US, citizen or not.

15th Amendment (1870)

“The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.”

- Removed race as a barrier to voting.

- Did not advance the voting rights of women. The 19th Amendment gave women the vote in 1920 after years of advocacy.

Priorities of Freedom

America was founded on revolutionary principles: the right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, democracy, and equality. These were not just abstract concepts. They represented what people believed they deserved, just because they were Americans.

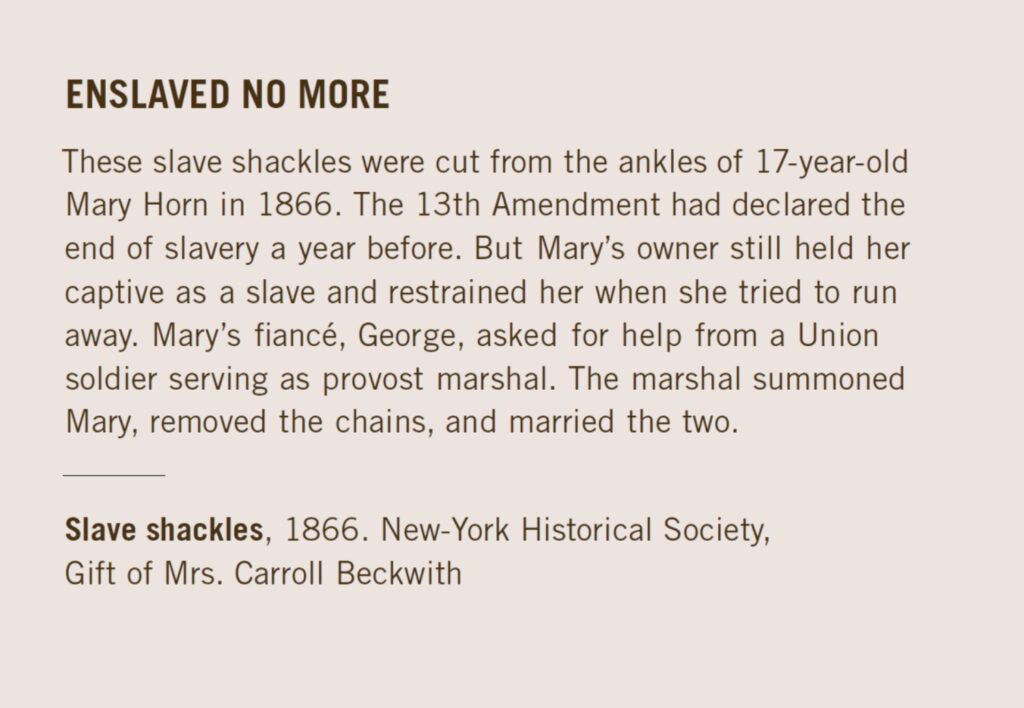

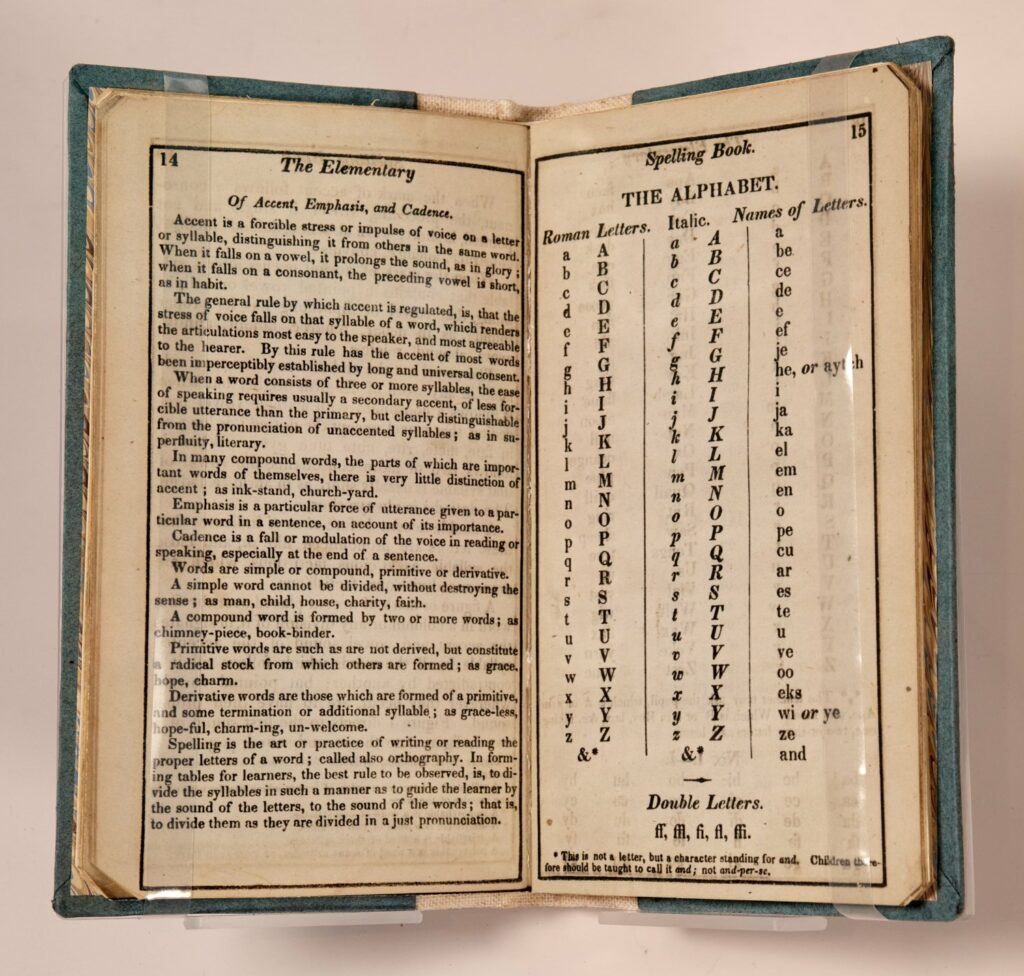

After the war, African Americans could claim these rights and freedoms for the first time, and they took steps they had previously only dreamed of. Some actions were profound, such as voting, or reuniting with family members who had been sold, or learning to read. Other steps were simple but liberating, like visiting a friend without the permission of a white person, or resting instead of working. All were a reminder of how radically different their lives were now.

But significant hazards lay ahead. As black people claimed new privileges, many Southern whites felt threatened and wronged, and they sometimes turned violent. In the North, racial segregation already limited black lives, and would grow more far-reaching in the decades ahead.

LIFE

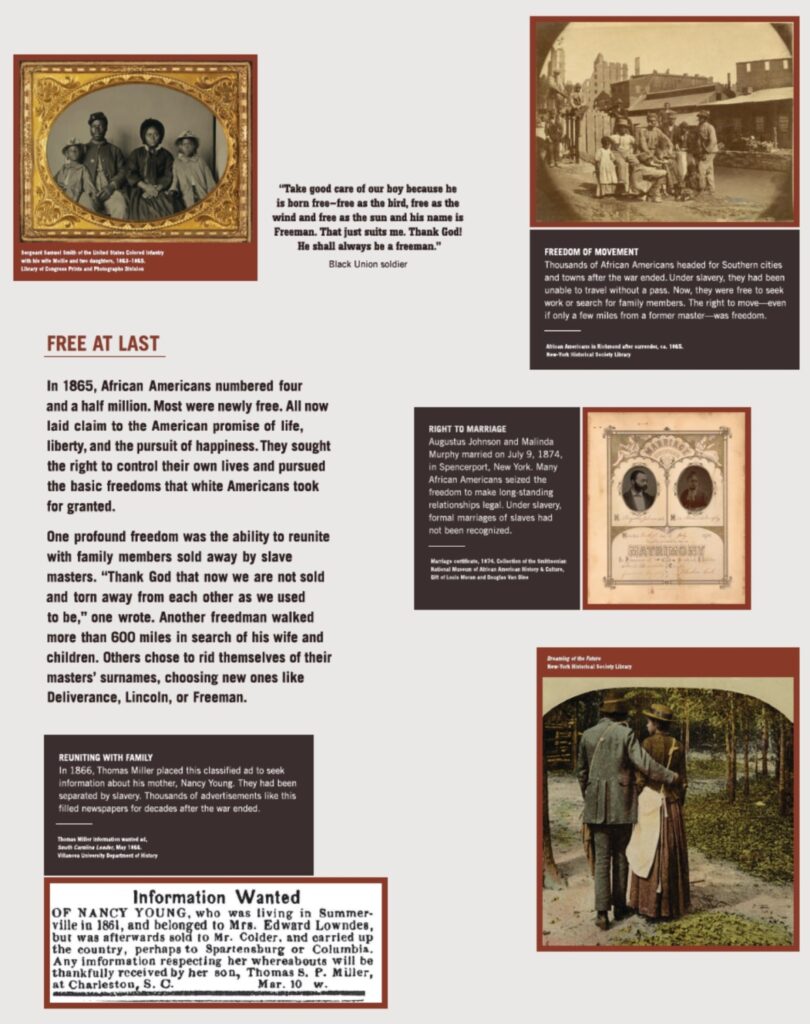

Free At Last

In 1865, African Americans numbered four and a half million. Most were newly free. All now laid claim to the American promise of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. They sought the right to control their own lives and pursued the basic freedoms that white Americans took for granted.

One profound freedom was the ability to reunite with family members sold away by slave masters. “Thank God that now we are not sold and torn away from each other as we used to be,” one wrote. Another freedman walked more than 600 miles in search of his wife and children. Others chose to rid themselves of their masters’ surnames, choosing new ones like Deliverance, Lincoln, or Freeman.

LIBERTY

A Right to the Land

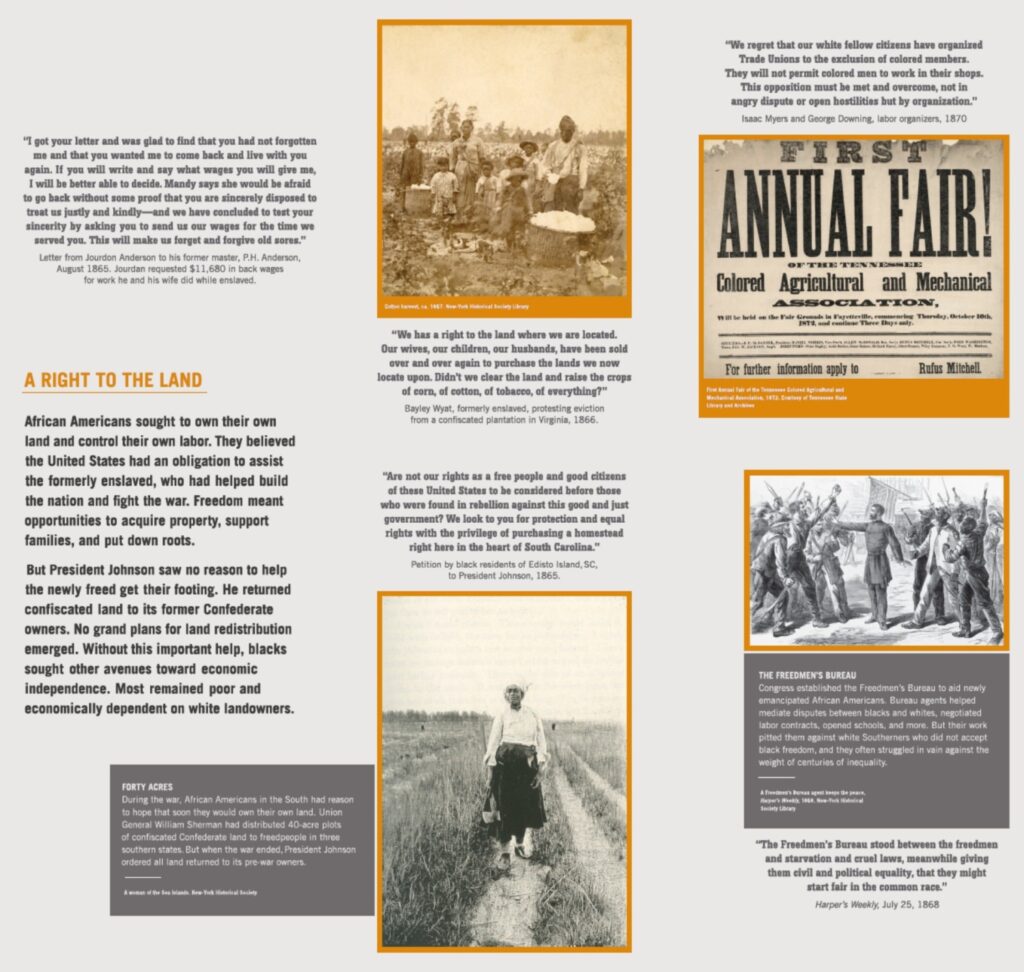

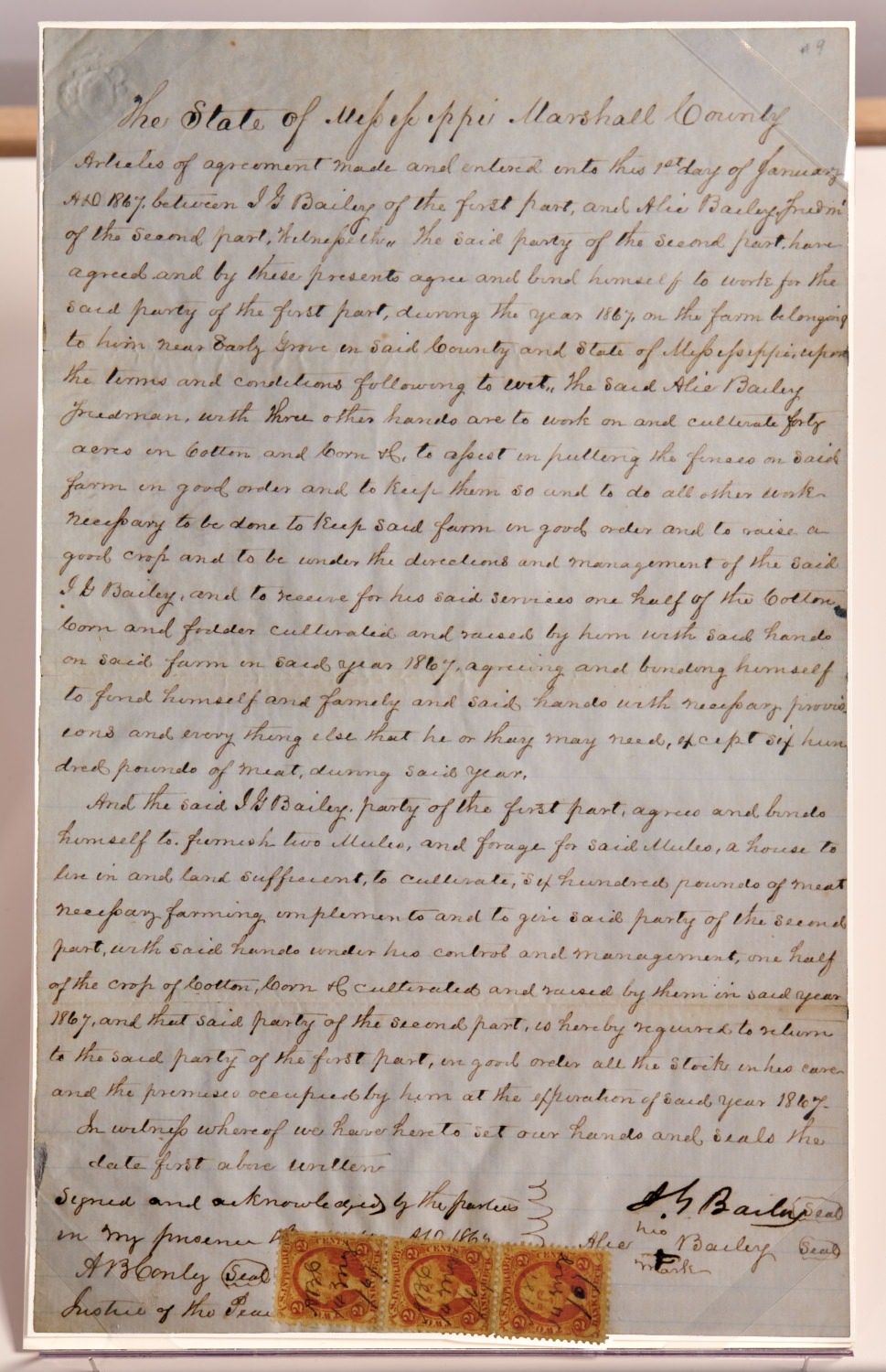

African Americans sought to own their own land and control their own labor. They believed the United States had an obligation to assist the formerly enslaved, who had helped build the nation and fight the war. Freedom meant opportunities to acquire property, support families, and put down roots.

But President Johnson saw no reason to help the newly freed get their footing. He returned confiscated land to its former Confederate owners. No grand plans for land redistribution emerged. Without this important help, blacks sought other avenues toward economic independence. Most remained poor and economically dependent on white landowners.

PURSUIT OF HAPPINESS

Education and Worship

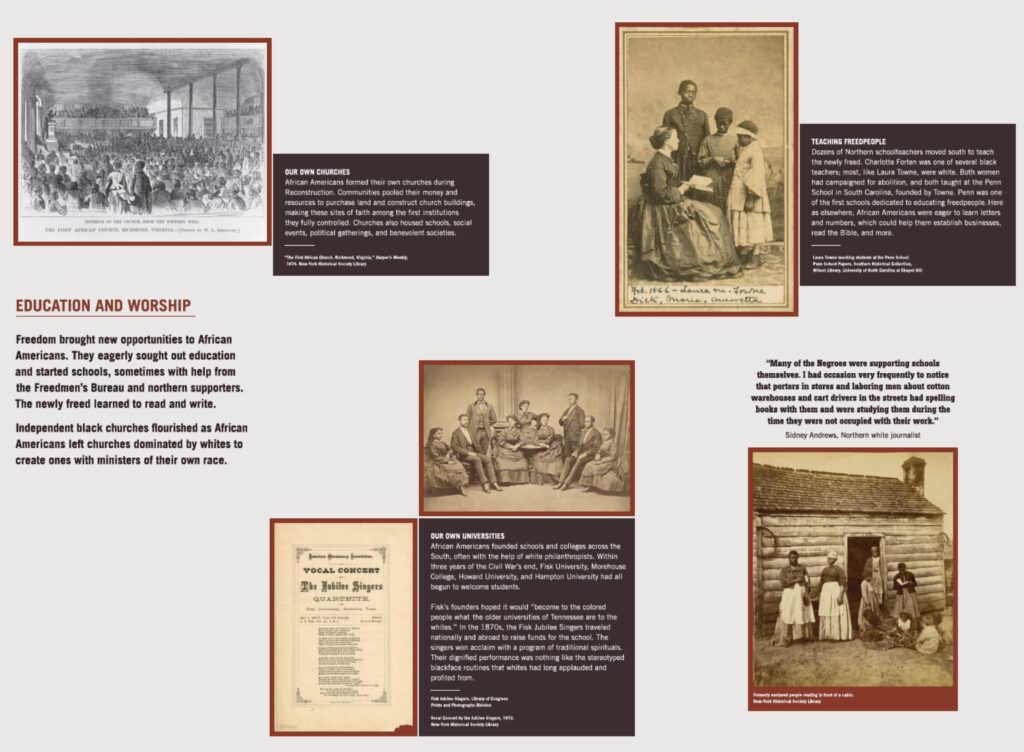

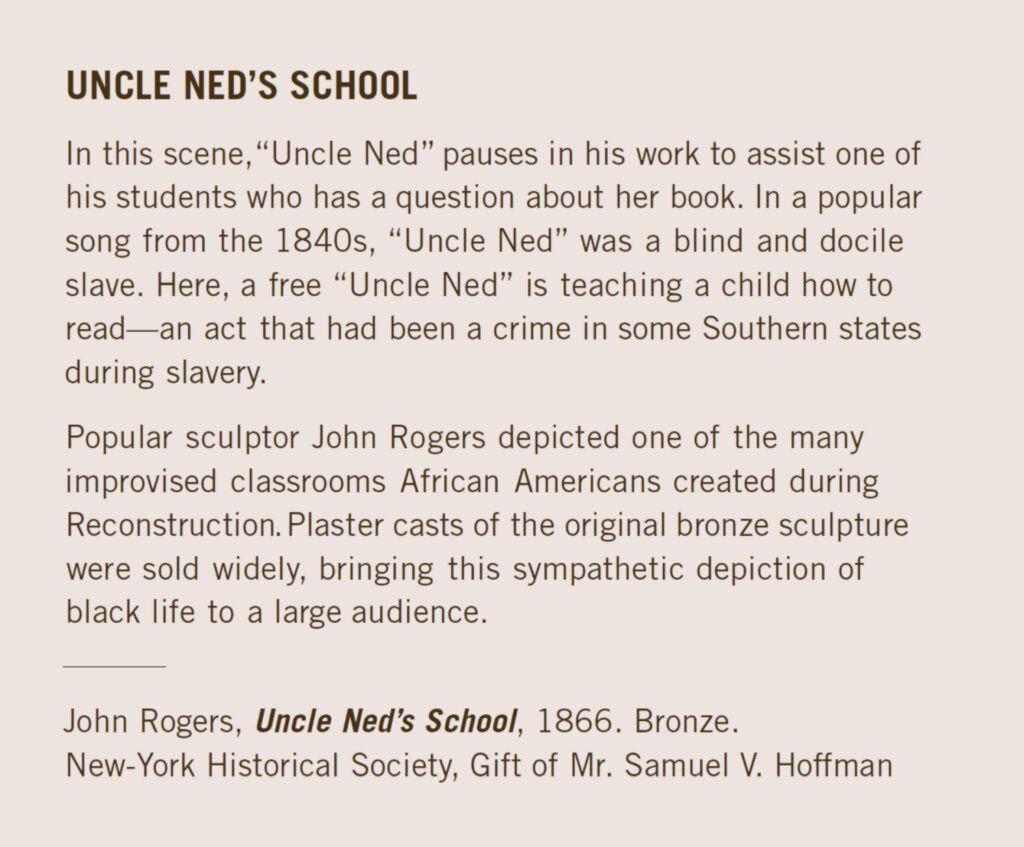

Freedom brought new opportunities to African Americans. They eagerly sought out education and started schools, sometimes with help from the Freedmen’s Bureau and northern supporters. The newly freed learned to read and write.

Independent black churches flourished as African Americans left churches dominated by whites to create ones with ministers of their own race.

DEMOCRACY

By the People

African Americans embraced their newly acquired citizenship and took seriously their long-denied rights and responsibilities. In large and small ways, they engaged in the political process.

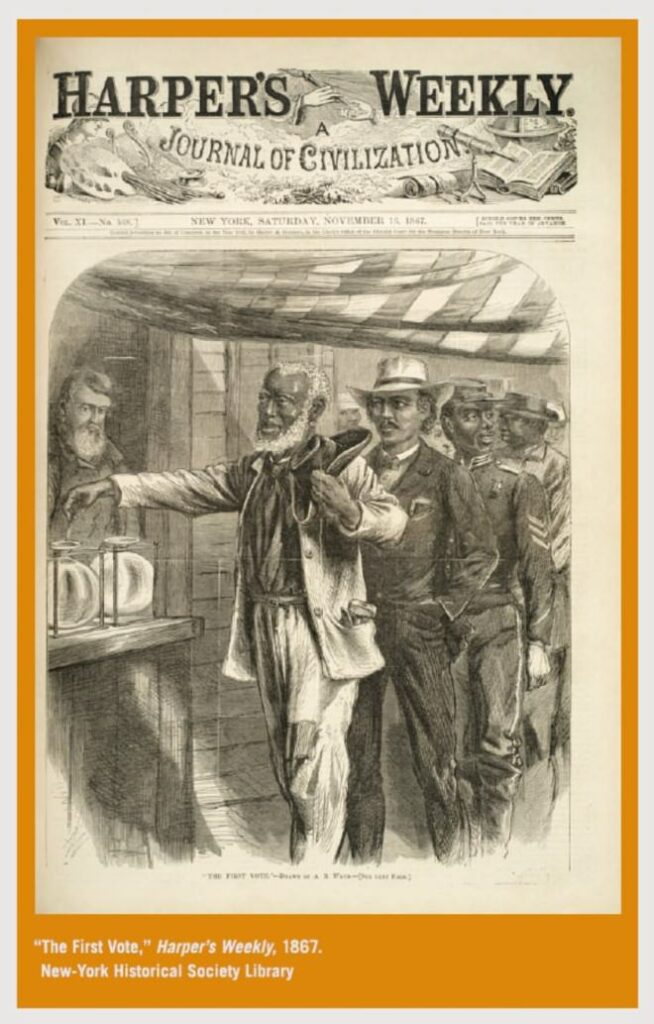

Black men voted in large numbers and ran for office. Men and women joined patriotic clubs and local branches of the Republican Party. Black participation in local elections and state constitutional conventions created the first interracial governments in the United States.

This demonstration of black citizenship aroused deep hostility among those who had only a few years earlier held African Americans as slaves.

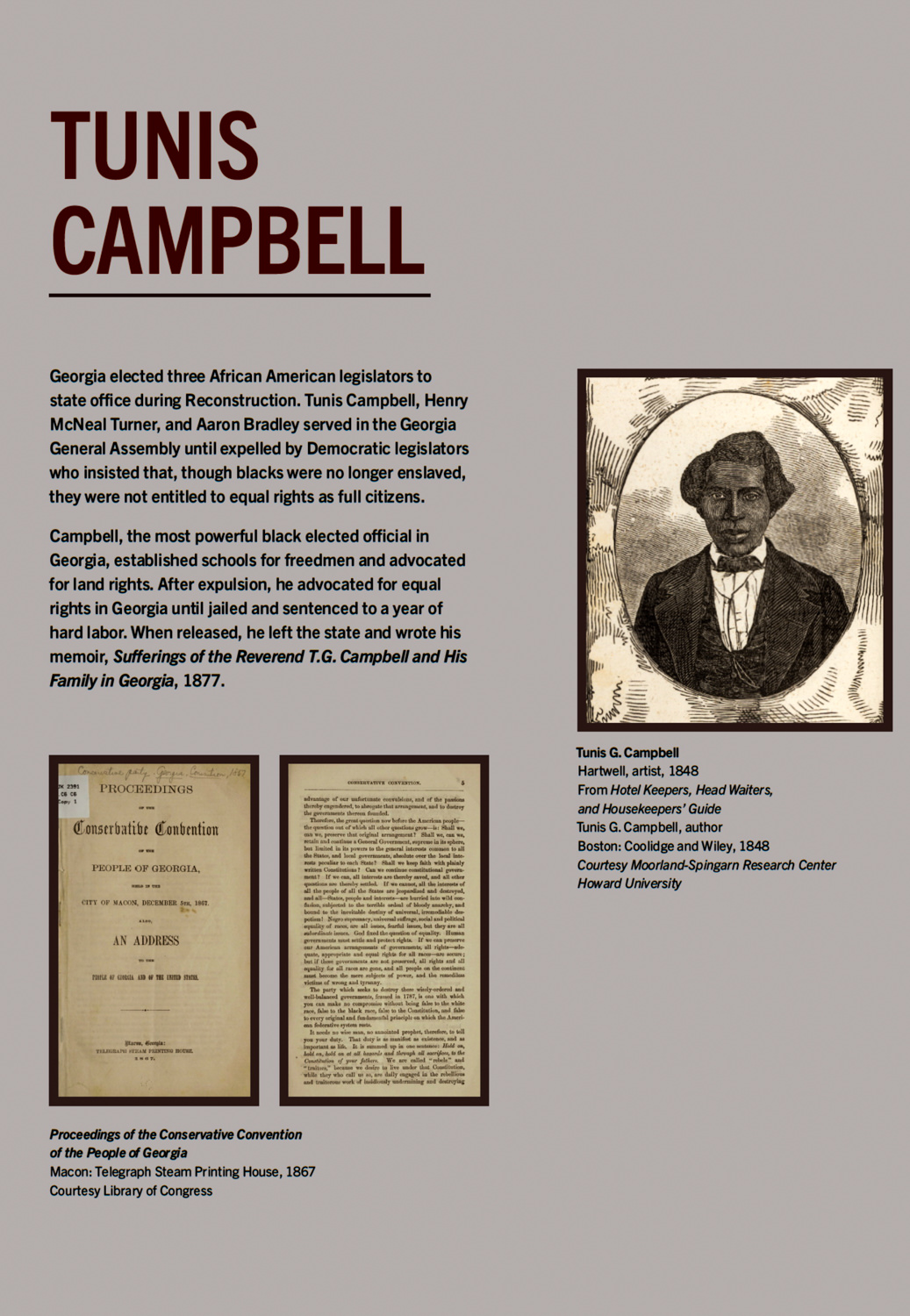

Tunis Campbell

Georgia elected three African American legislators to state office during Reconstruction. Tunis Campbell, Henry McNeal Turner, and Aaron Bradley served in the Georgia General Assembly, until expelled by Democratic legislators who insisted that, though blacks were no longer enslaved, they were not entitled to equal rights as full citizens.

Campbell, the most powerful black elected official in Georgia, established schools for freedmen and advocated for land rights. After expulsion, he advocated for equal rights in Georgia until jailed and sentence to a year of hard labor. When released, he left the state and wrote his memoir, Sufferings of the Reverend T.G. Campbell and His Family in Georgia, 1877.

EQUALITY

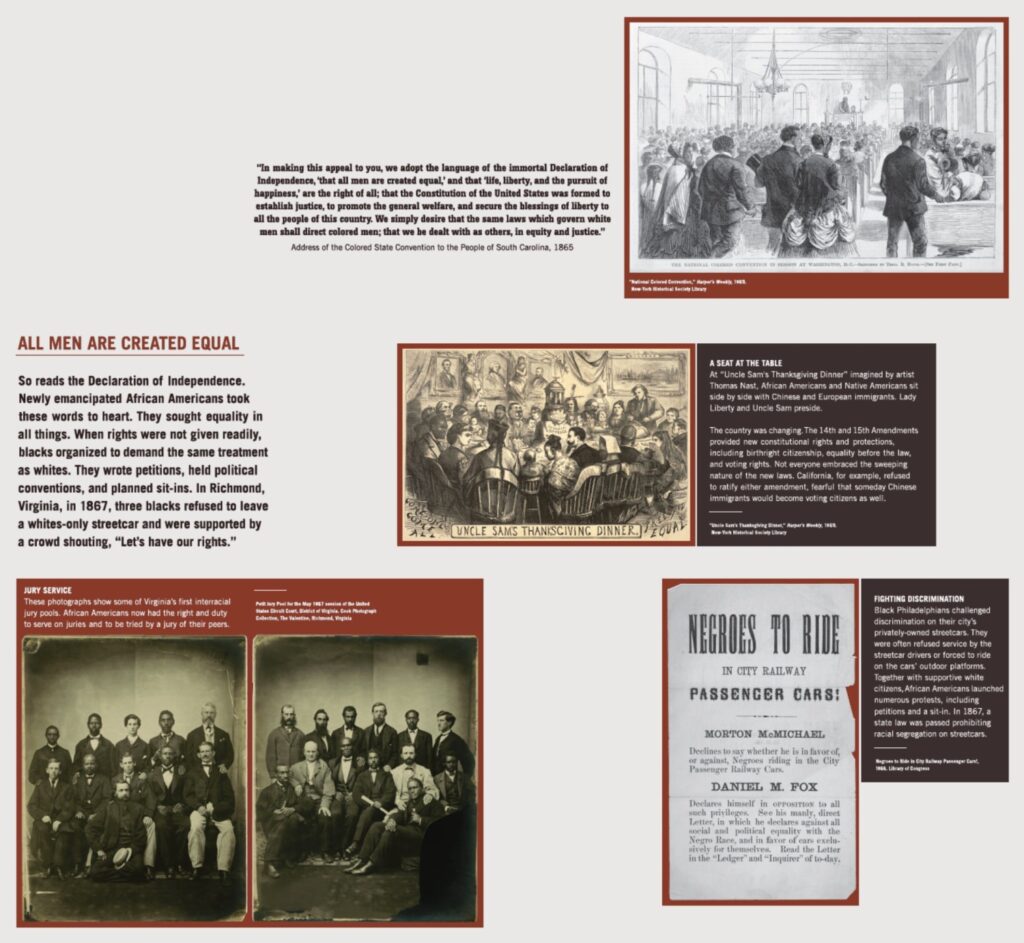

All Men Are Created Equal

So reads the Declaration of Independence. Newly emancipated African Americans took these words to heart. They sought equality in all things. When rights were not given readily, blacks organized to demand the same treatment as whites. They wrote petitions, held political conventions, and planned sit-ins. In Richmond, Virginia, in 1867, three blacks refused to leave a whites-only streetcar and were supported by a crowd shouting, “Let’s have our rights.”

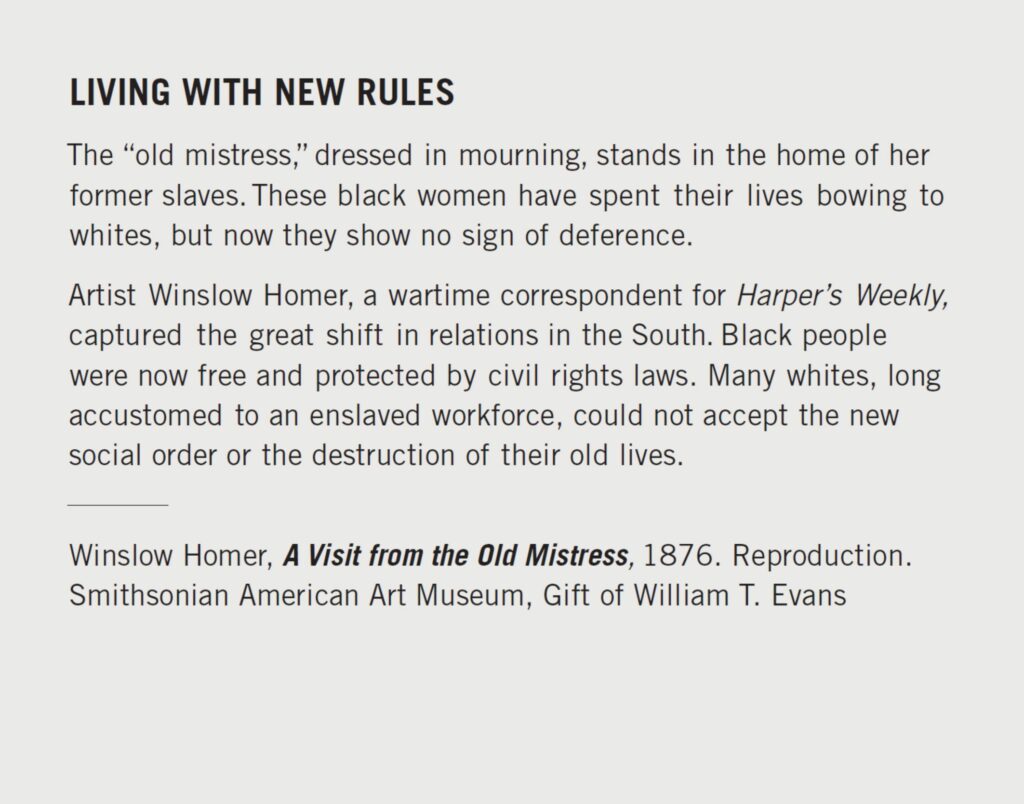

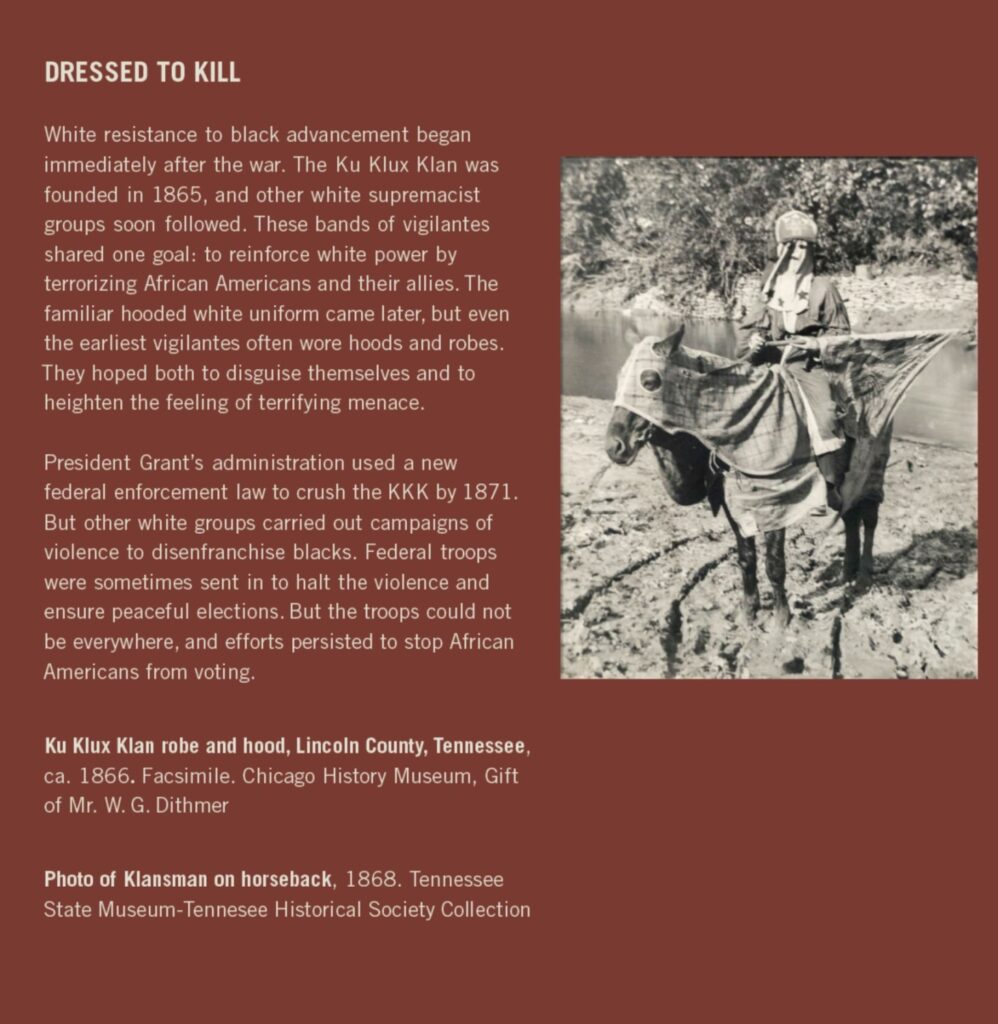

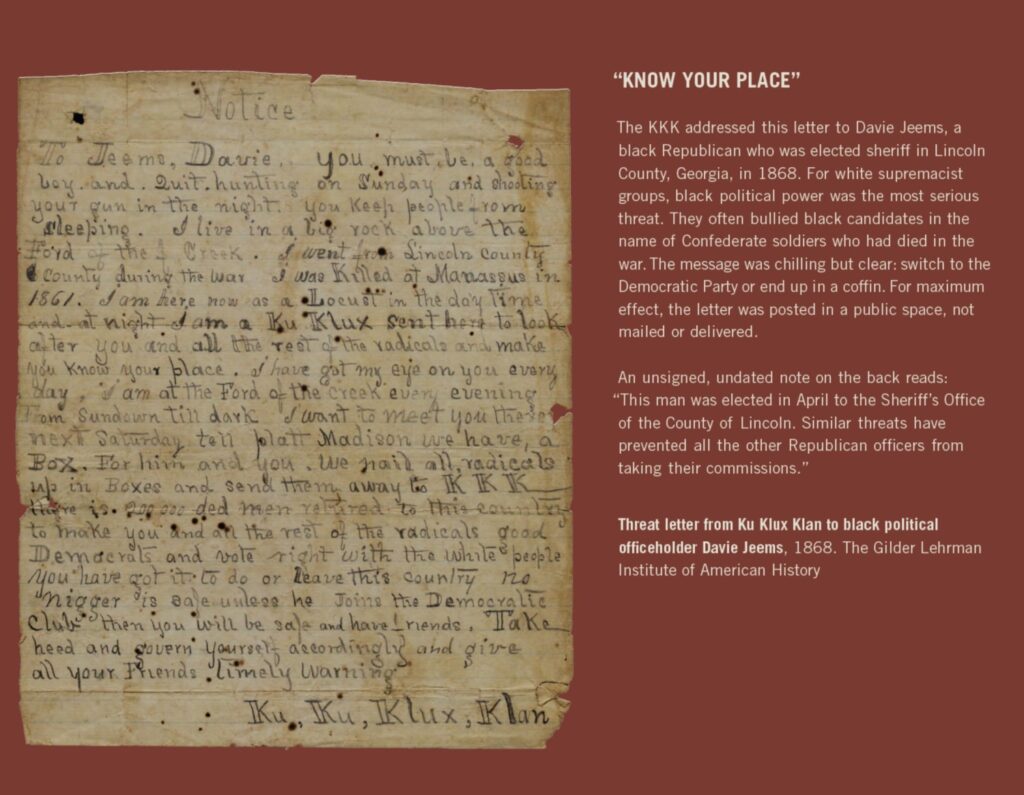

Dressed to Kill

White resistance to black advancement began immediately after the war. The Ku Klux Klan was founded in 1865, and other white supremacist groups soon followed. These bands of vigilantes shared one goal: to reinforce white power by terrorizing African Americans and their allies. The familiar hooded white uniform came later, but even the earliest vigilantes often wore hoods and robes. They hoped both to disguise themselves and to heighten the feeling of terrifying menace.

President Grant’s administration used a new federal enforcement law to crush the KKK by 1871. But other white groups carried out campaigns of violence to disenfranchise blacks. Federal troops were sometimes sent in to halt the violence and ensure peaceful elections. But the troops could not be everywhere, and efforts persisted to stop African Americans from voting.

Reconstruction Abandoned

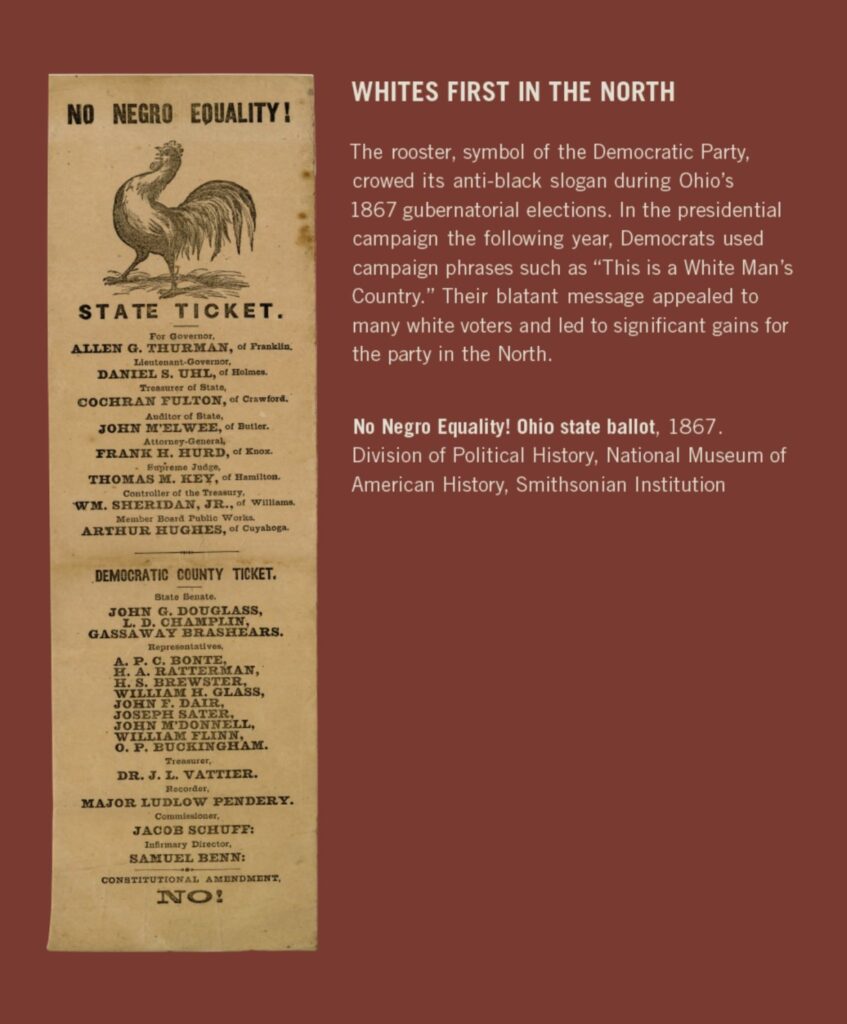

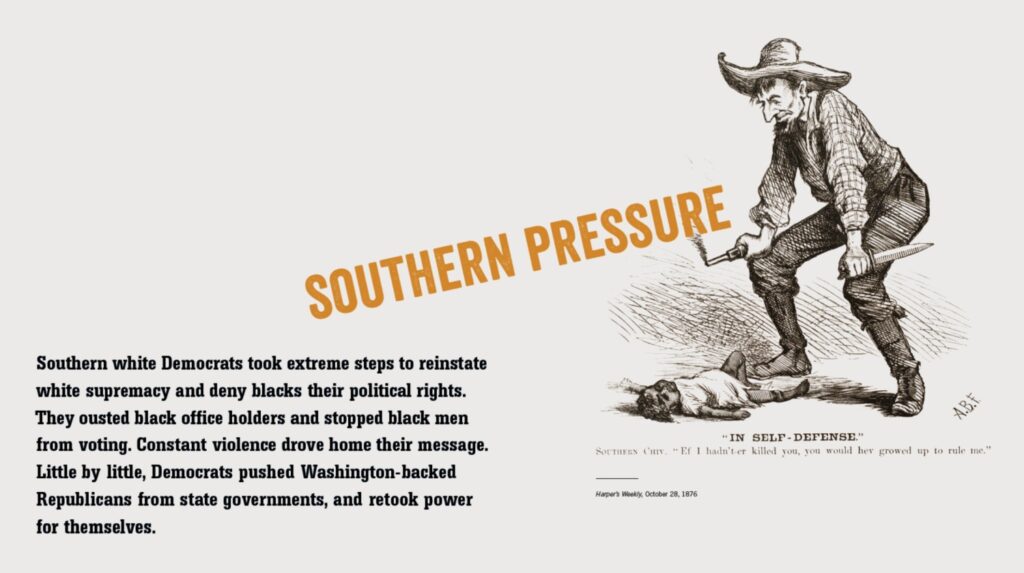

Southern Pressure

Southern white Democrats took extreme steps to reinstate white supremacy and deny blacks their political rights. They ousted black office holders and stopped black men from voting. Constant violence drove home their message. Little by little, Democrats pushed Washington-backed Republicans from state governments, and retook power for themselves.

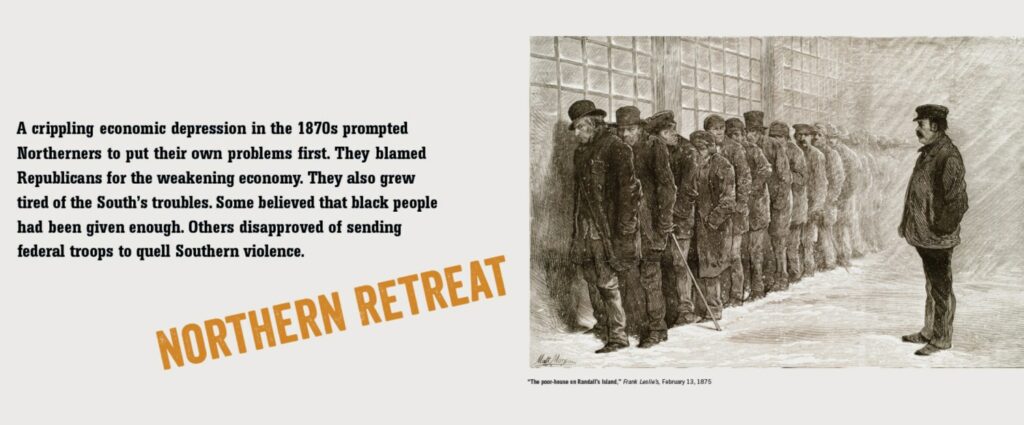

Northern Retreat

A crippling economic depression in the 1870s prompted Northerners to put their own problems first. They blamed Republicans for the weakening economy. They also grew tired of the South’s troubles. Some believed that black people had been given enough. Others disapproved of sending federal troops to quell Southern violence.

Compromise of 1877

The 1876 presidential election was inconclusive. Congress had to settle the matter, and politicians struck a deal. Democrats allowed Republican Rutherford B. Hayes to become president. Republicans agreed to withdraw federal troops from the South. This compromise ended formal Reconstruction in 1877, twelve years after it began.

Without the presence of the US military, and with the Supreme Court setting new limits on constitutional protections for blacks, federal power over the South dwindled. Washington grew largely unable to defend the rights of African Americans. Former Confederate states began to undo the gains of Reconstruction.

“You have emancipated us. You have enfranchised us. And I thank you for it. But what is your emancipation—what is your enfranchisement if the black man is unable to exercise that freedom? You have turned us loose to the sky, to the storm, to the whirlwind, and worst of all, you have turned us loose to our infuriated masters. The question now is, do you mean to make good to us the promises in your constitution?”

–Frederick Douglass, 1876