The Atlanta University Complex

This display created by

The Atlanta University Complex

In the wake of the Civil War, more than 4.5 million black Southerners looked to start new lives as full citizens of the country they labored for generations to build. Some fled north, hoping for new opportunities to work, be educated, and escape violence they suffered in the South. Others made a home where they were, farming rural plots to earn a living for themselves and their families. A large number believed they could achieve progress in Southern cities and towns, especially those promising jobs, schools, and established black communities.

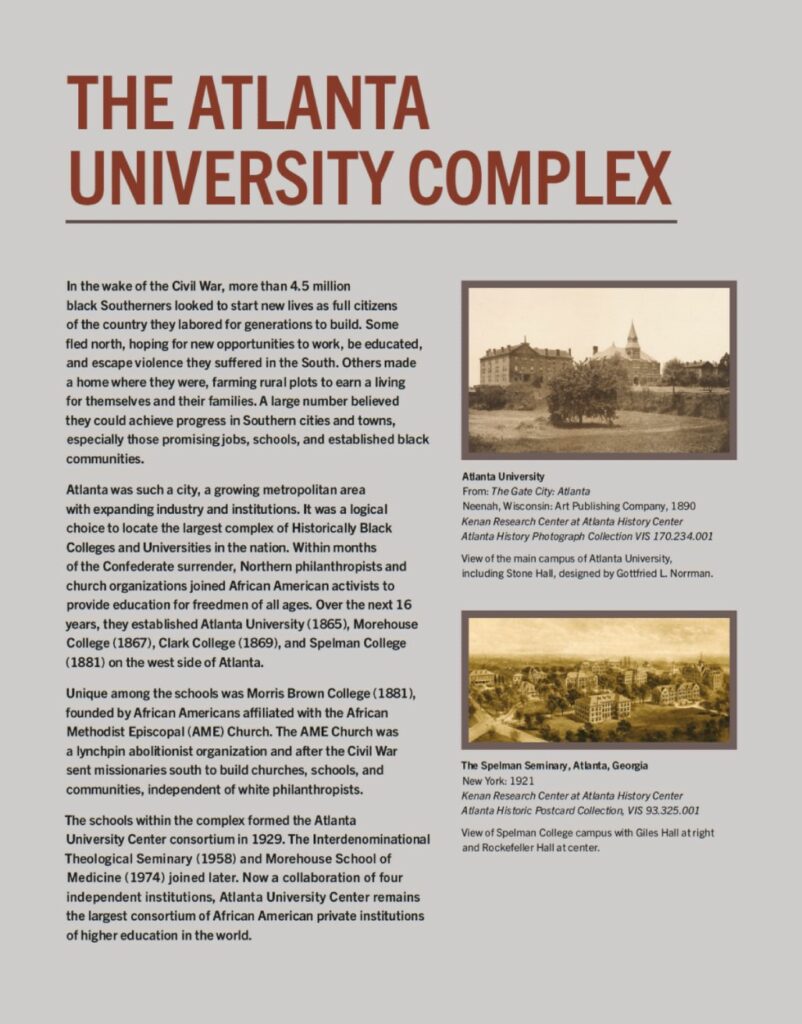

Atlanta was such a city, a growing metropolitan with expanding industry and institutions. It was a logical choice to locate the largest complex of Historically Black Colleges and Universities in the nation. Within months of the Confederate surrender, Northern philanthropists and church organizations joined African American activists to provide education for freedmen of all ages. Over the next 16 years, they established Atlanta University (1865), Morehouse College (1867), Clark College (1869), and Spelman College (1881) on the west side of Atlanta.

Unique among the schools was Morris Brown College (1881), founded by African Americans affiliated with the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church. The AME Church was a lynchpin abolitionist organization and after the Civil War sent missionaries to build churches, schools, and communities, independent of white philanthropists.

The schools within the complex formed the Atlanta University Center consortium in 1929. The Interdenominational Theological Seminary (1958) and Morehouse Schools of Medicine (1974) joined later. Now a collaboration of four independent institutions, Atlanta University Center remains the largest consortium of African American private institutions of higher education in the world.

Each One, Teach One

The term “citizenship” often indicates a range of civil rights. Full citizenship suggests equal economic opportunity, voting rights, fair treatment under the law, and respect for cultural expression. Education is a critical tool for identifying, fighting for, and exercising these rights.

For the first 250 years of American history, enslaved people were barred from formal education. Even free blacks had limited access to schooling. Following the Civil War, Georgia was typical of Southern states and provided few resources for even elementary school education after Reconstruction ended in 1877.

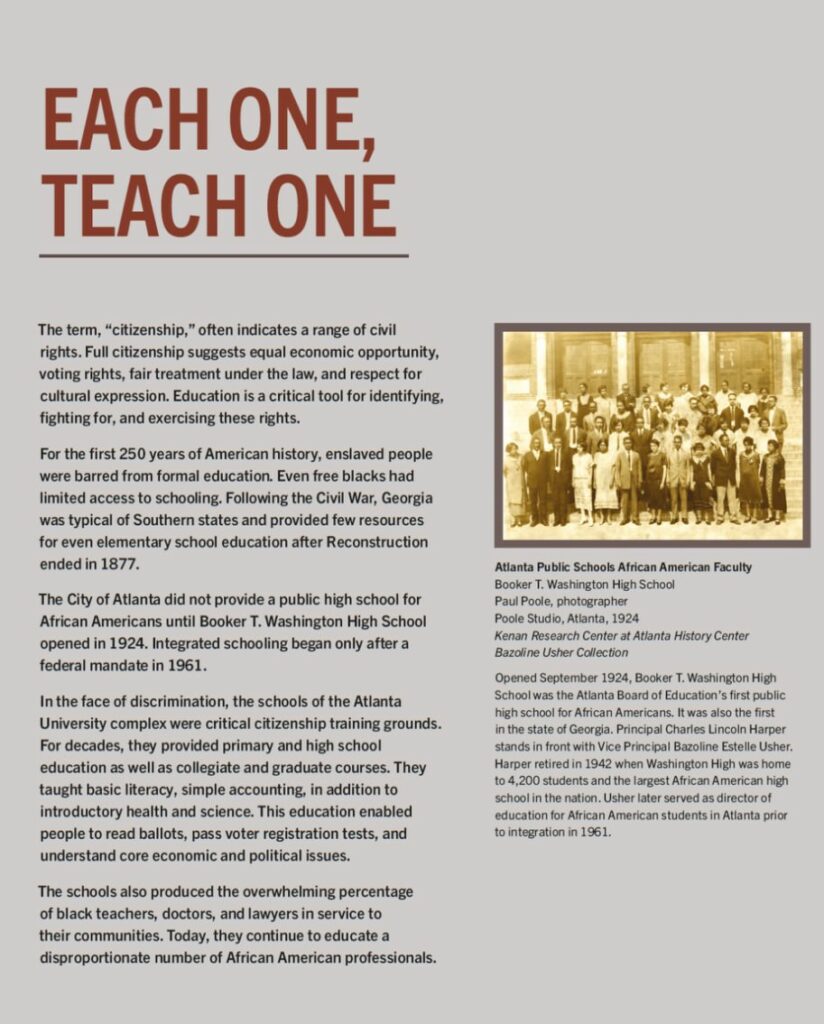

The City of Atlanta did not provide a public high school for African Americans until Booker T. Washington High School opened in 1924. Integrated schooling began only after a federal mandate in 1961.

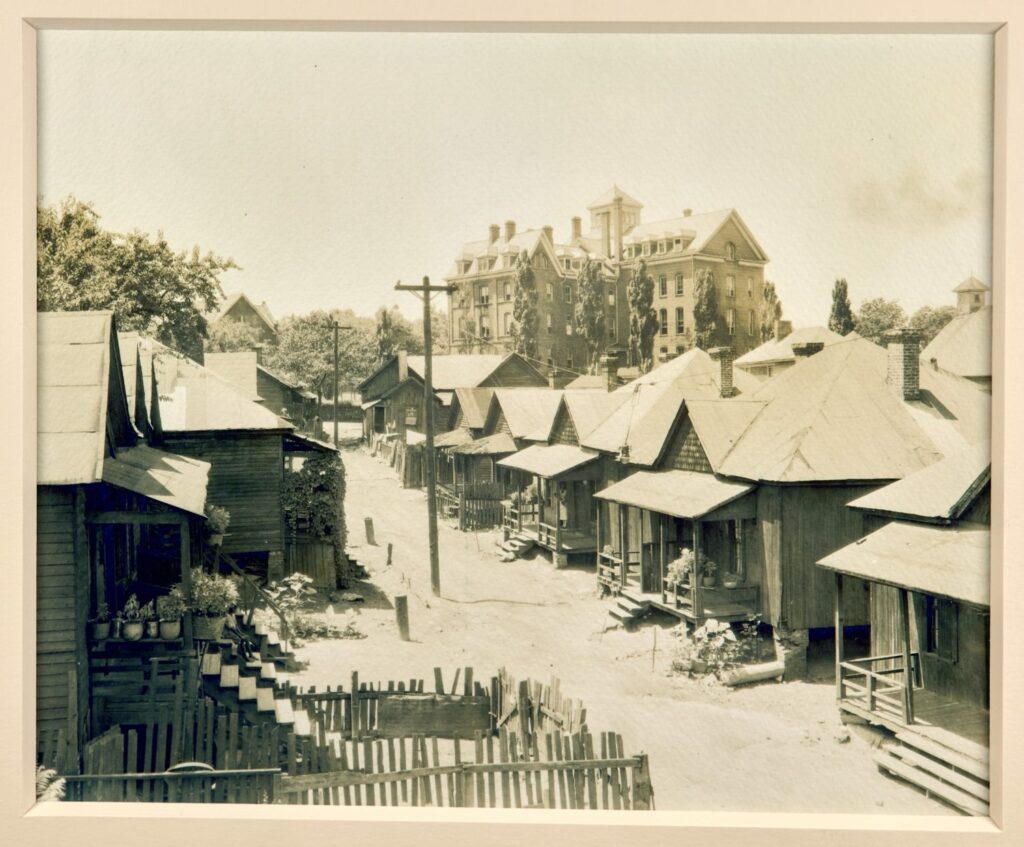

In the face of discrimination, the schools of the Atlanta University complex were critical citizenship training grounds. For decades, they provided primary and high school education as well as collegiate and graduate courses. They taught basic literacy, simple accounting, in addition to introductory health and science. This education enabled people to read ballots, pass voter registration tests, and understand core economic and political issues.

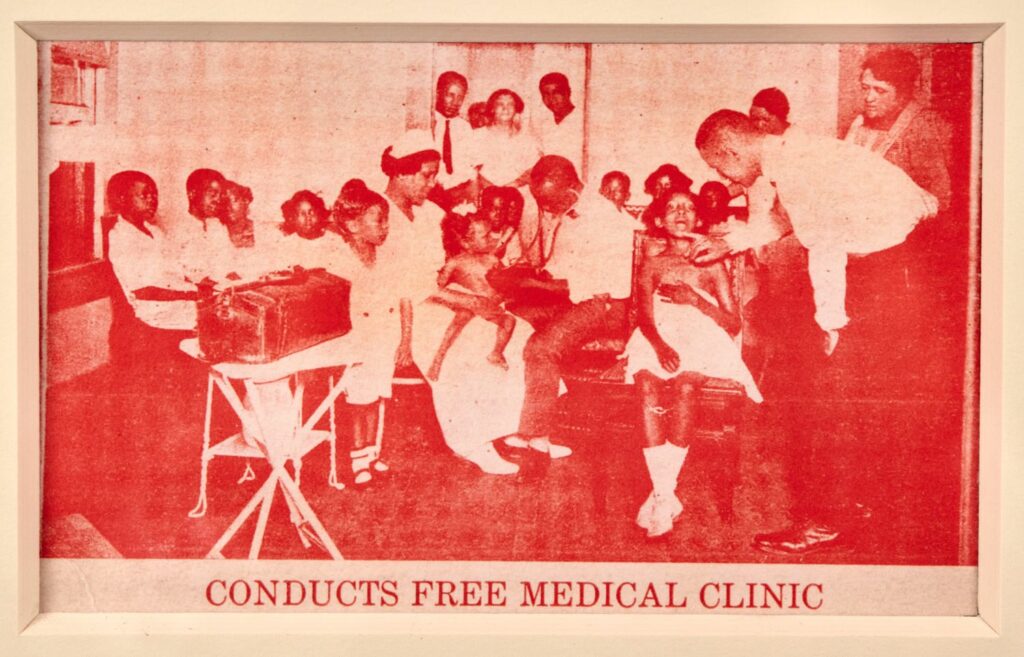

The schools also produced the overwhelming percentage of black teachers, doctors, and lawyers in service to their communities. Today, they continue to educate a disproportionate number of African American professionals.

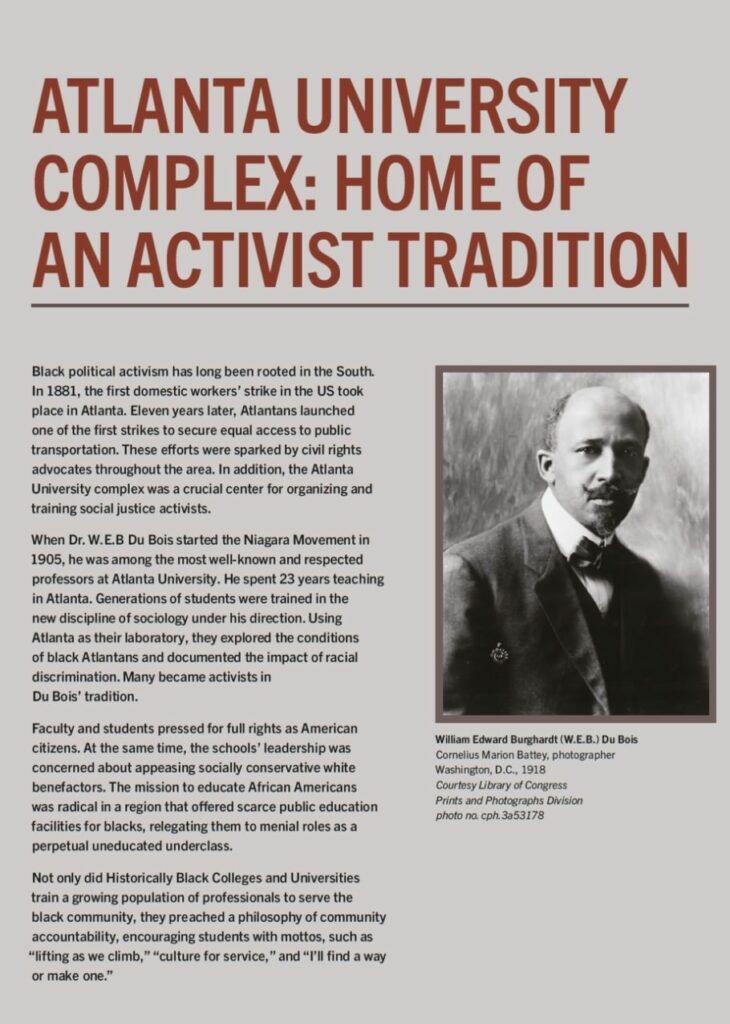

Atlanta University Complex: Home of an Activist Tradition

Black political activism has long been rooted in the South. In 1881, the first domestic workers’ strike in the U.S. took place in Atlanta. Eleven years later, Atlantans launched one of the first strikes to secure equal access to public transportation. These efforts were sparked by civil rights advocates throughout the area. In addition, the Atlanta University complex was a crucial center for organizing and training social justice activists.

When Dr. W.E.B. Du Bois started the Niagara Movement in 1905, he was among the most well-known and respected professors at Atlanta University. He spent 23 years teaching in Atlanta. Generations of students were trained in the new discipline of sociology under his direction. Using Atlanta as their laboratory, they explore the conditions of black Atlantans and documented the impact of racial discrimination. Many became activists in Du Bois’ tradition.

Faculty and students pressed for full rights as American citizens. At the same time, the schools’ leadership was concerned about appeasing socially conservative white benefactors. The mission to educate African Americans was radical in a region that offered scarce public education facilities for blacks, relegating them to menial roles as a perpetual uneducated underclass.

Not only did Historically Black Colleges and Universities train a growing population of professionals to serve the black community, they preached a philosophy of community accountability, encouraging students with mottos, such as “lifting as we climb,” “culture for service,” and “I’ll find a way or make one.”

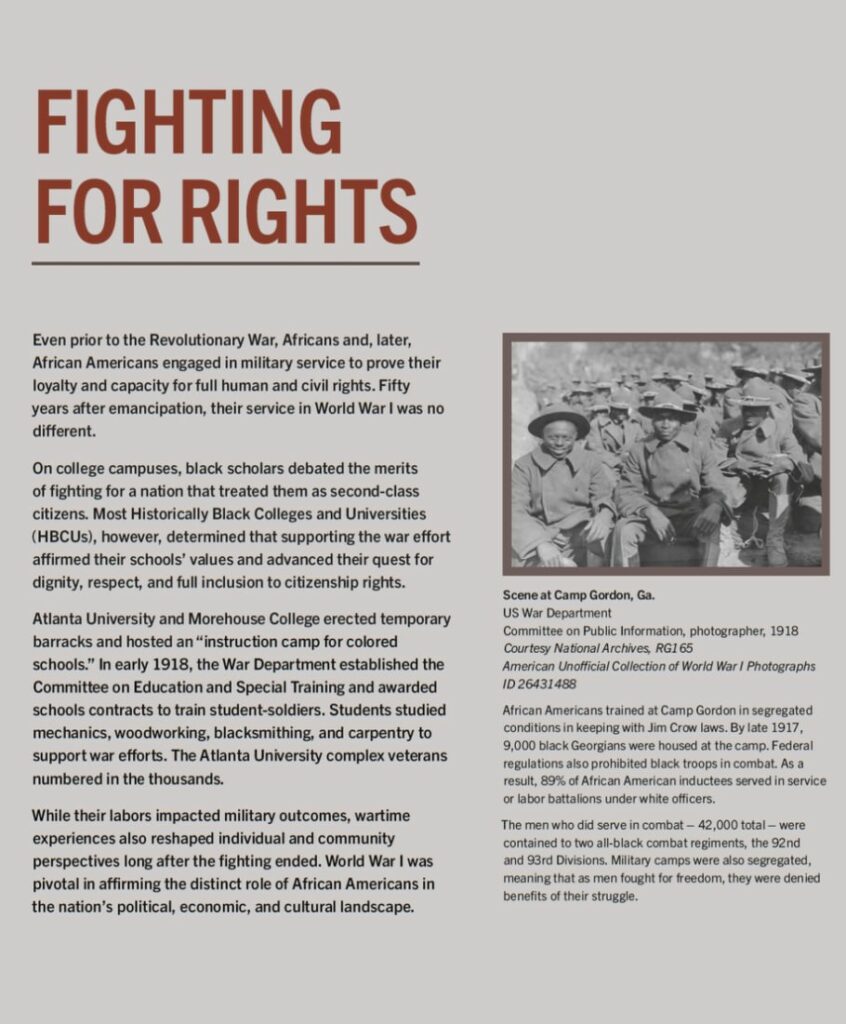

Fighting for Rights

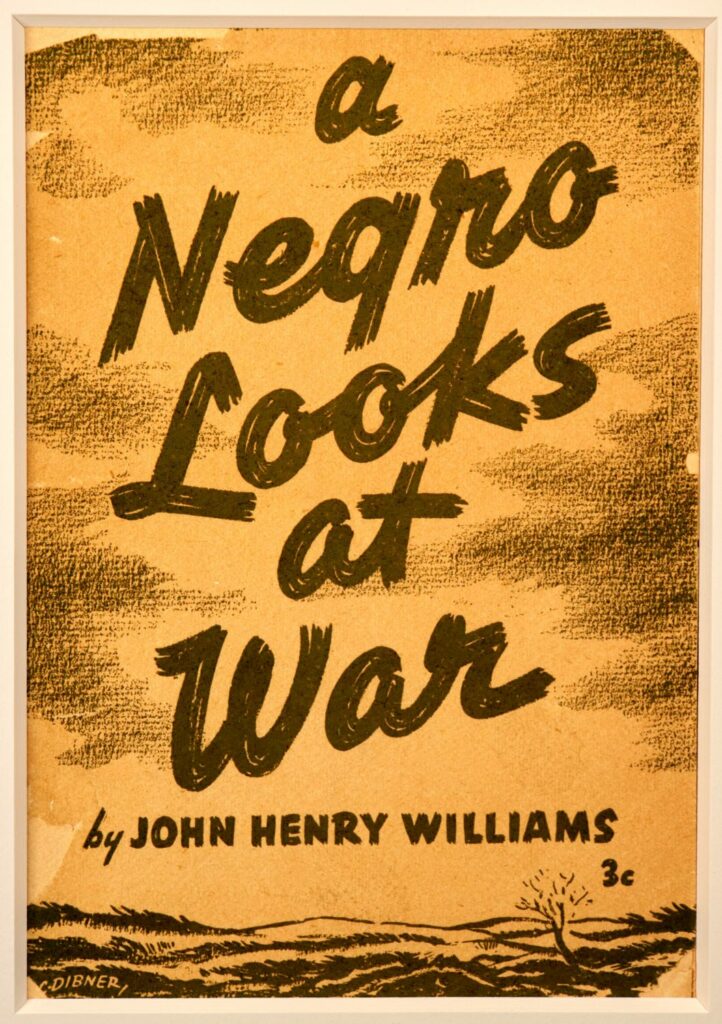

Even prior to the Revolutionary War, Africans and, later, African Americans engaged in military service to prove their loyalty and capacity for full human and civil rights. Fifty years after emancipation, their service in World War I was no different.

On college campuses, black scholars debated the merits of fighting for a nation that treated them as second-class citizens. Most Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs), however, determined that supporting the war effort affirmed their schools’ values and advanced their quest for dignity, respect, and full inclusion to citizenship rights.

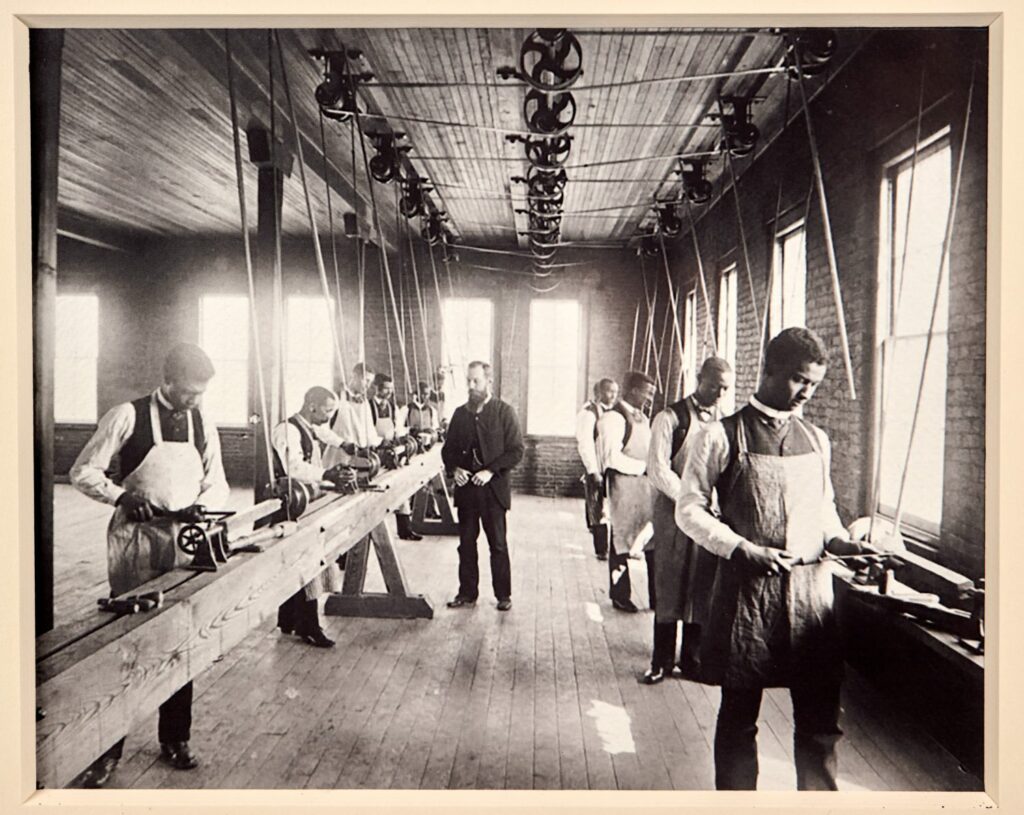

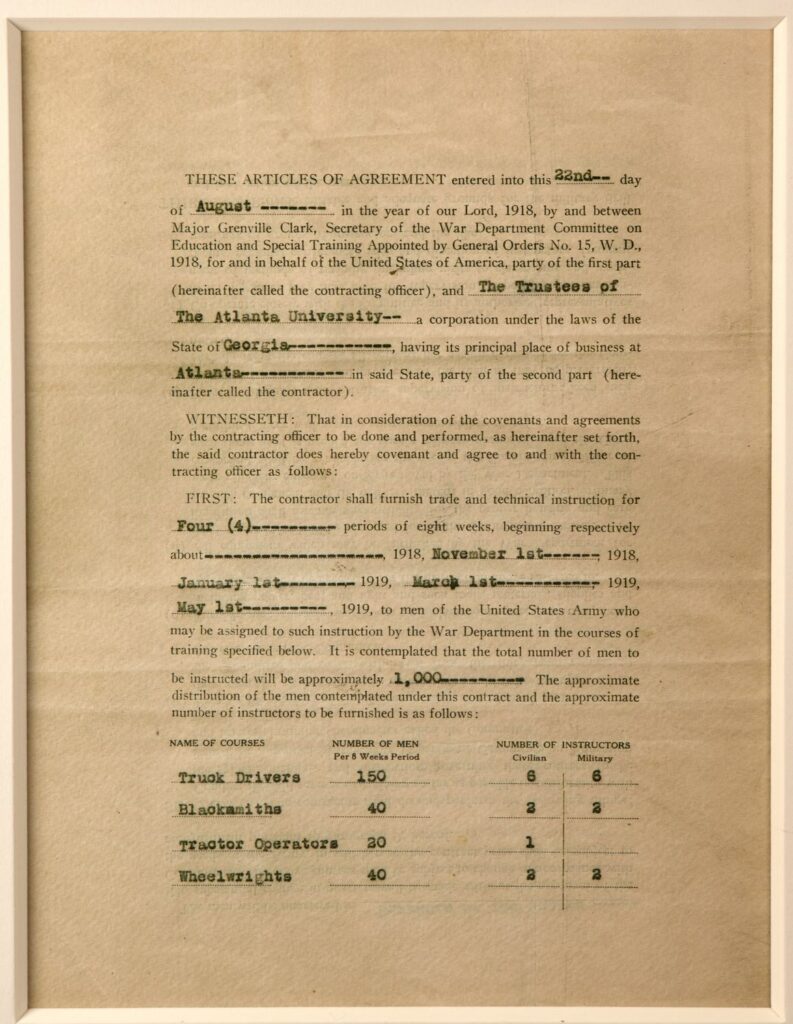

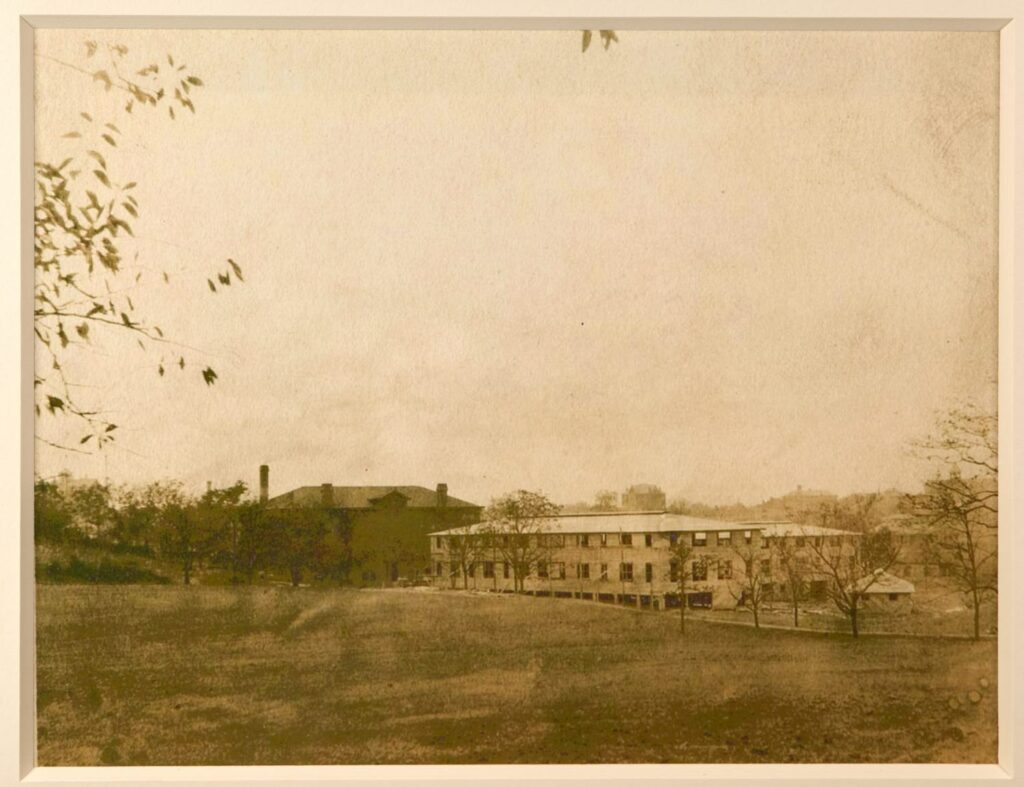

Atlanta University and Morehouse College erected temporary barracks and hosted an “instruction camp for colored schools.” In early 1918, the War Department established the Committee on Education and Special Training and awarded schools contracts to train student-soldiers. Students studied mechanics, woodworking, blacksmithing, and carpentry to support war efforts. The Atlanta University complex veterans numbered in the thousands.

While their labors impacted military outcomes, wartime experiences also reshaped individual and community perspectives long after the fighting ended. World War I was pivotal in affirming the distinct role of African Americans in the nation’s political, economic, and cultural landscape.