Introduction

We the People

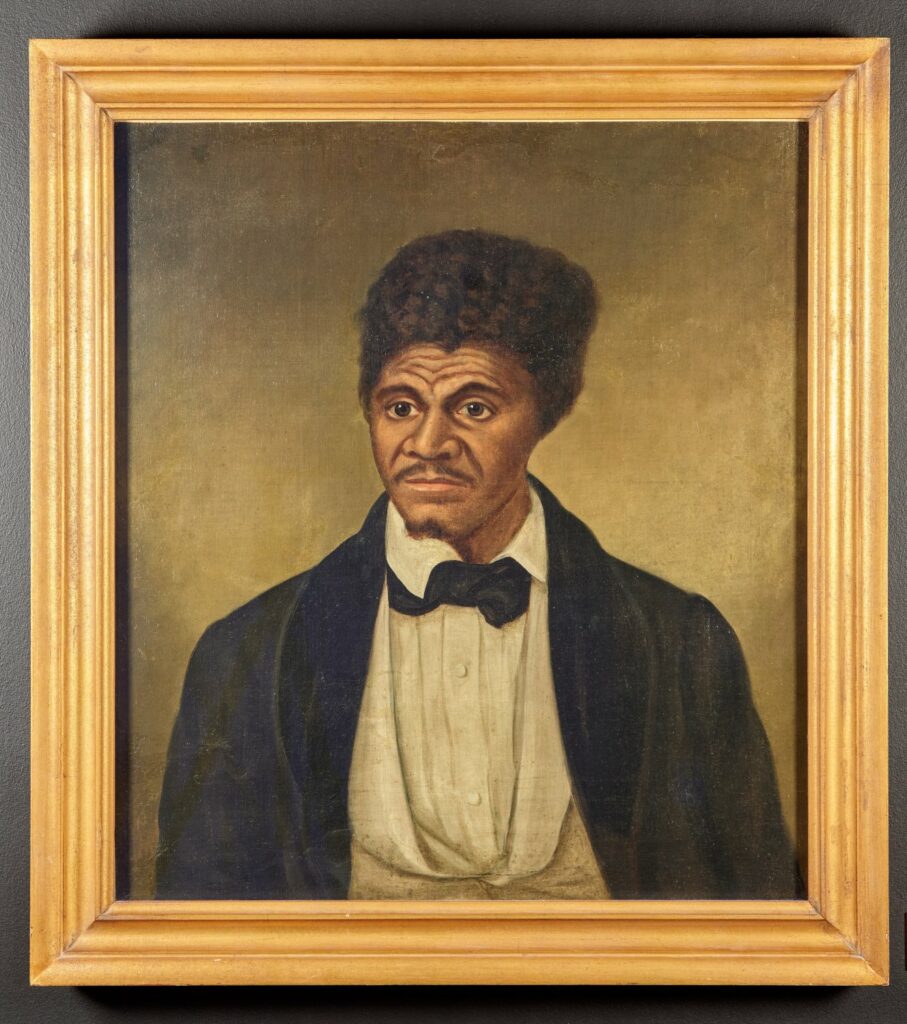

Dred Scott was a Missouri slave who sued for his freedom. He argued that he had lived with his master in the state of Illinois and the Wisconsin Territory, places where slavery was outlawed. Other slaves had been emancipated for this reason. But in 1857 the US Supreme Court decided against him. It said he had no right to sue because he was not a US citizen.

The justices ruled that no black person, free or enslaved, could ever be a US citizen.

American citizenship confers legal rights, protections, and responsibilities. But its meaning goes deeper. To be a citizen is to be accepted, to be “one of us.”

Black Americans have long fought for full membership in the American community. In this struggle, the years after the Civil War were critical. Freedom, citizenship, and the right to vote were all extended to African Americans. But by the early 1900s, a repressive racial system known as “Jim Crow” had sabotaged these liberties. This exhibit explores this half century of stunning advances and reversals.

War Over Slavery

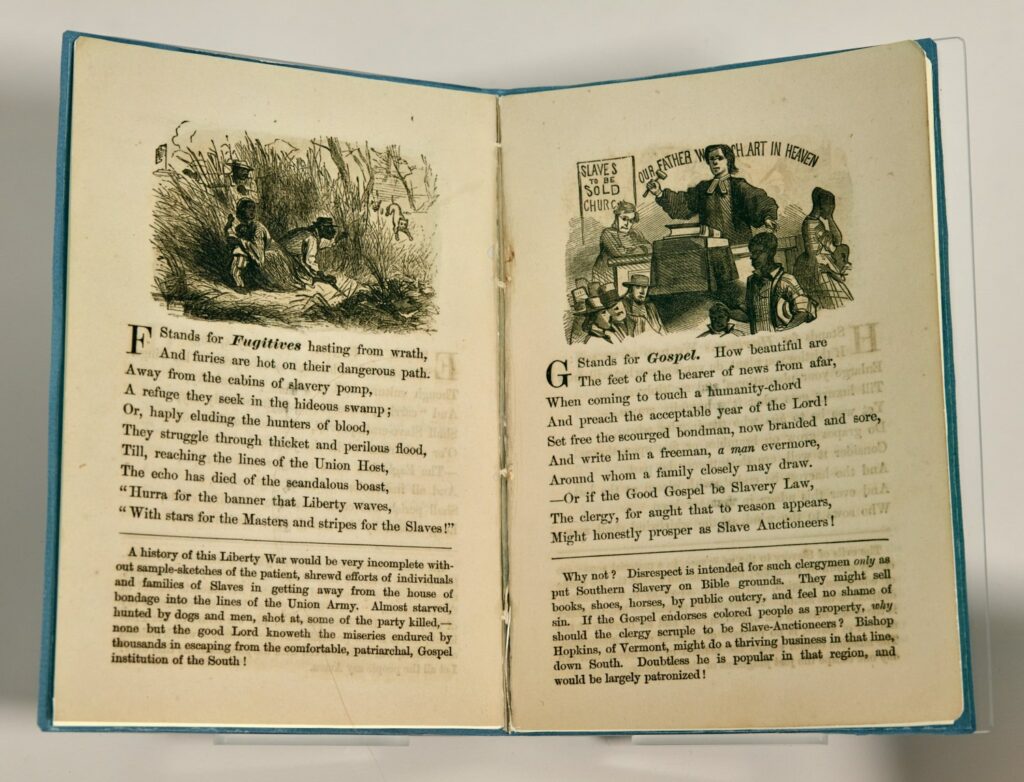

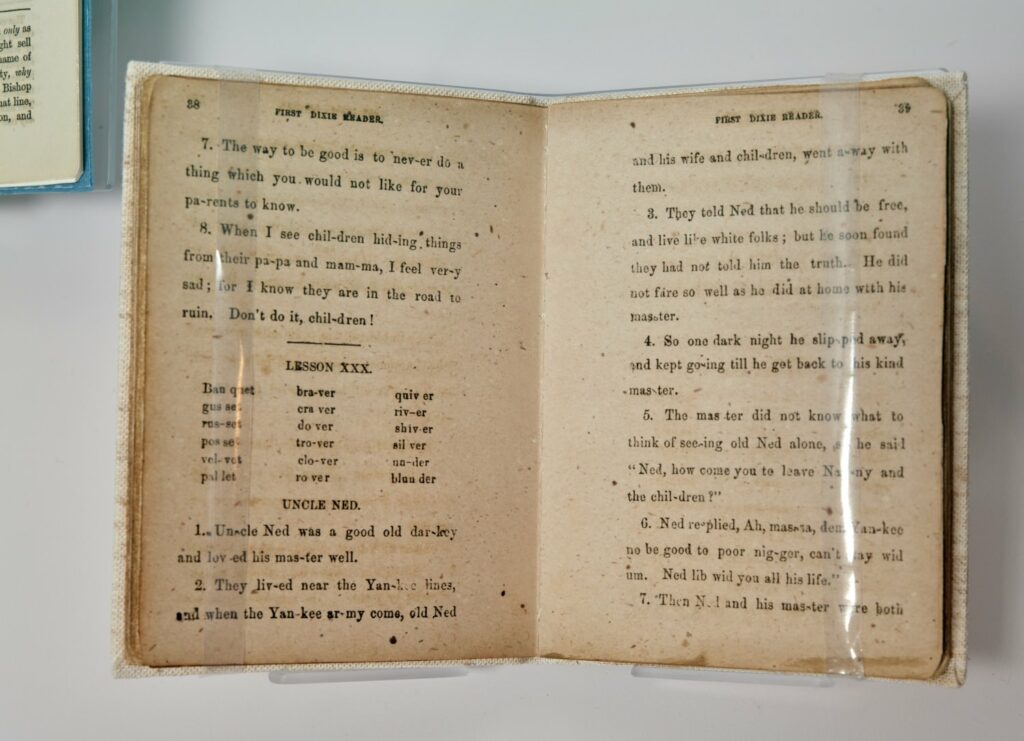

Slavery was legal in every American colony. In the aftermath of the American Revolution (1775–1783), most Northern states gradually abolished slavery. But many Southerners continued to see it as an economic necessity. Their reliance on slave labor produced a system that dehumanized blacks, ripped their families apart, and denied them their rights.

In the North, opposition to slavery continued to grow. Some Northerners fought to abolish the institution entirely. Others hoped only to contain it to the South.

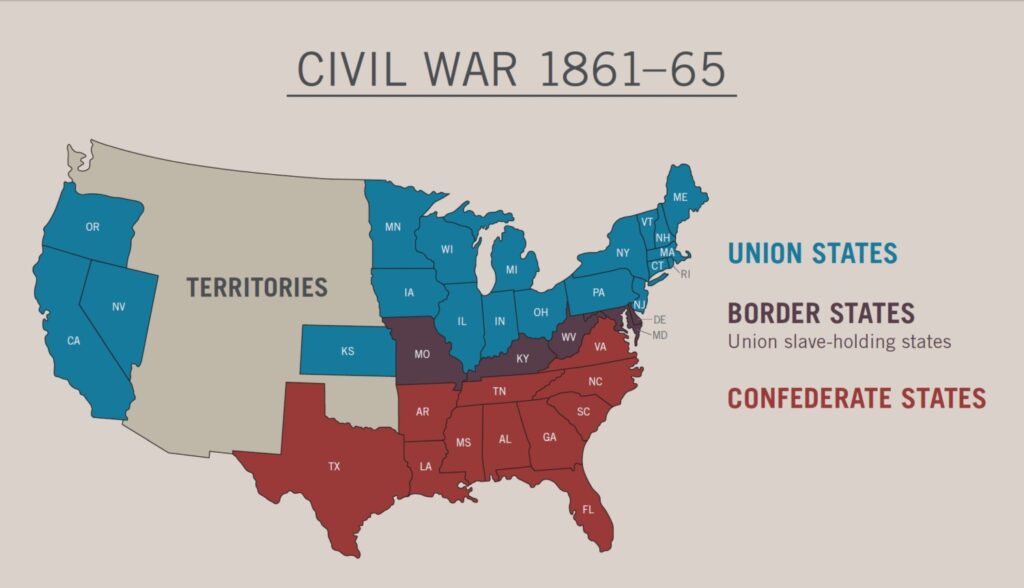

Many Southerners, by contrast, wanted slavery to expand into the western states and territories. When Abraham Lincoln was elected president in 1860 on a platform that rejected the spread of slavery, they saw it as a mortal threat. The Civil War erupted in 1861. Eleven states seceded from the Union and formed the Confederacy.

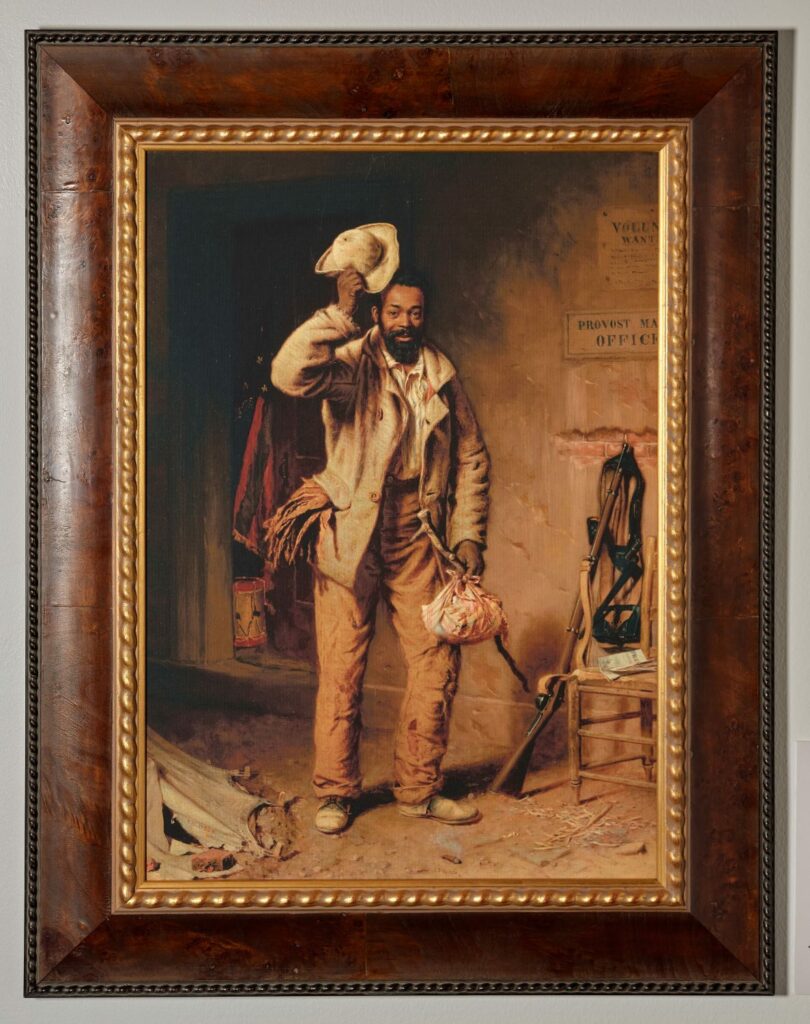

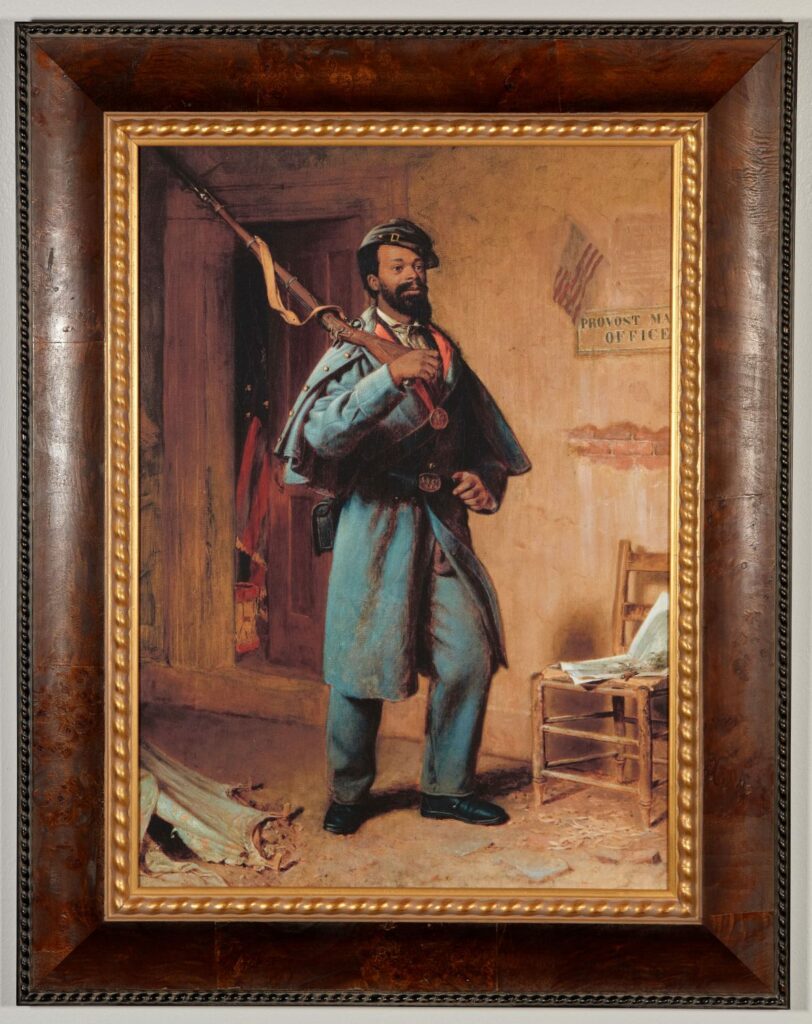

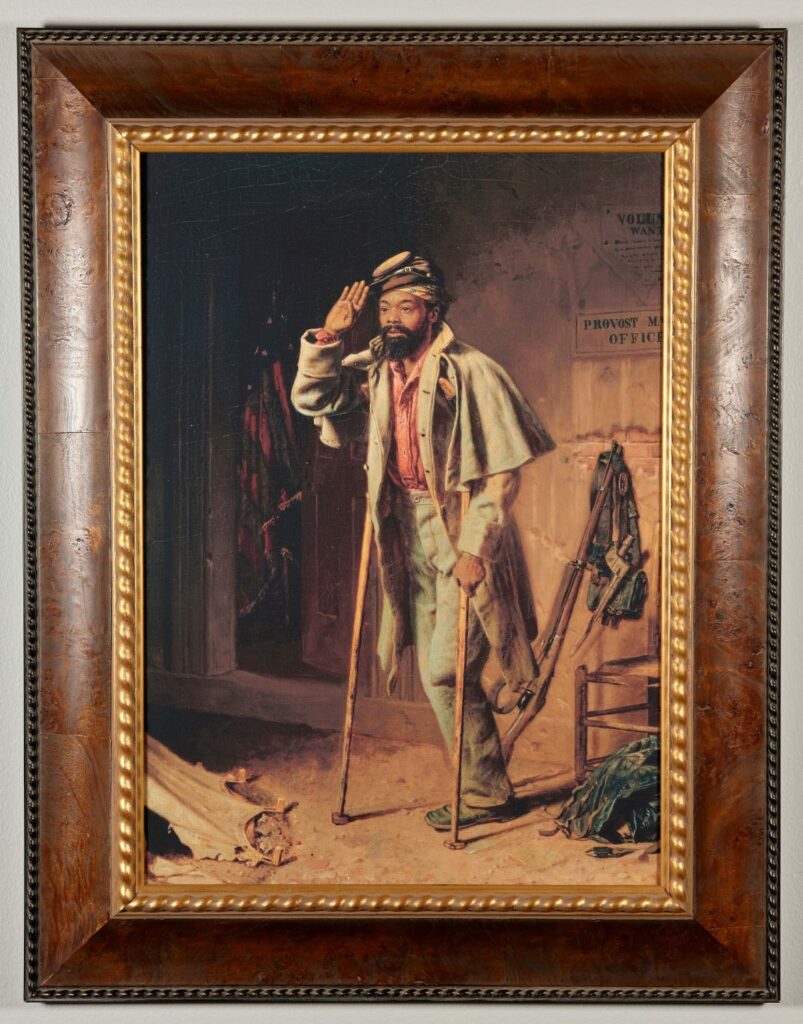

Forever Free

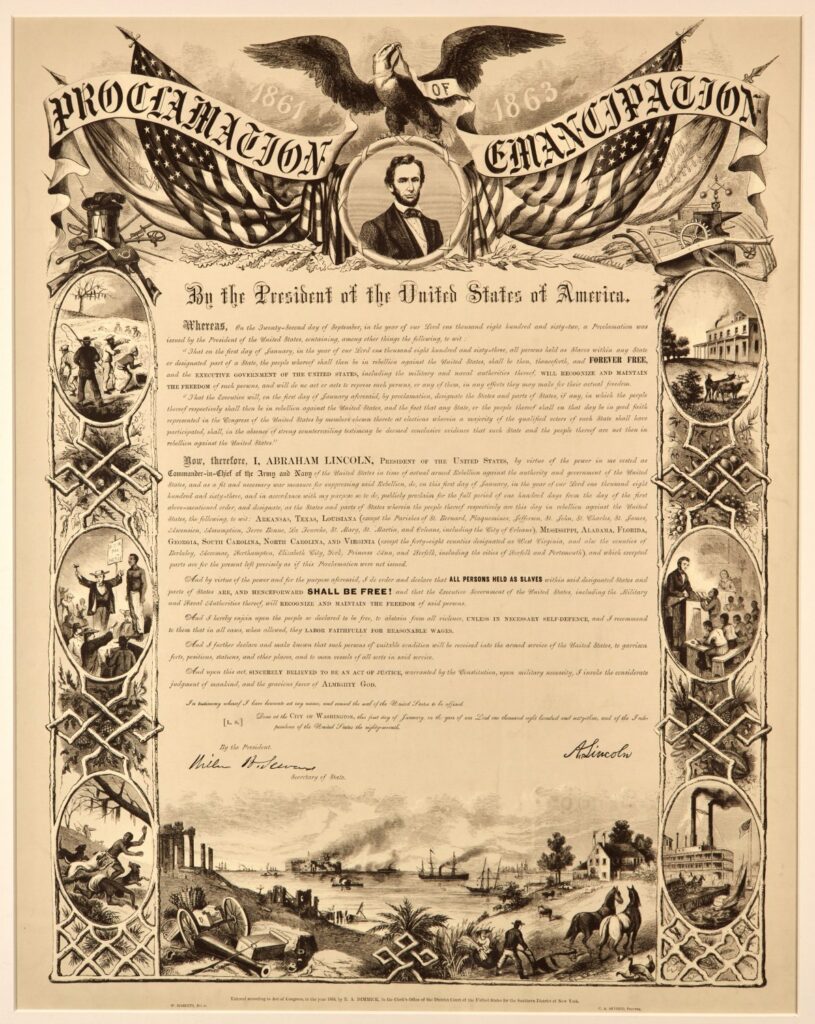

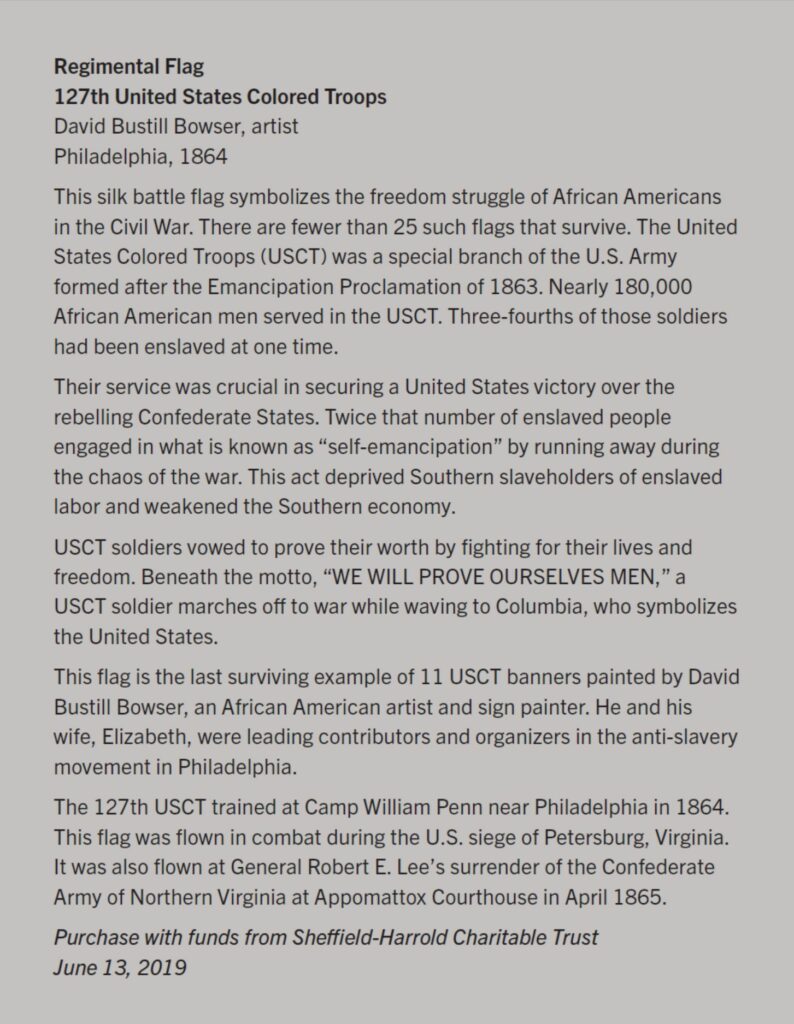

African Americans immediately volunteered to join the Union’s fight against the breakaway Confederacy. But they were not accepted into the military until midway through the war. The change came after the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863. President Lincoln declared that most persons held as slaves in the rebellious states “are, and henceforward shall be free.” His executive order made ending slavery a goal of the war, and it cleared the way for black men to join the Union Army and Navy.

In the Union North, black men joined up by the thousands. In the Confederate South and West, they fled north to enlist and were recruited where Union troops were victorious. In slave states that did not secede, special rules allowed for black enlistment even though slavery remained intact.

By the end of the war, African Americans made up ten percent of the Union Army. A third of those who served lost their lives.

Gaining Freedom

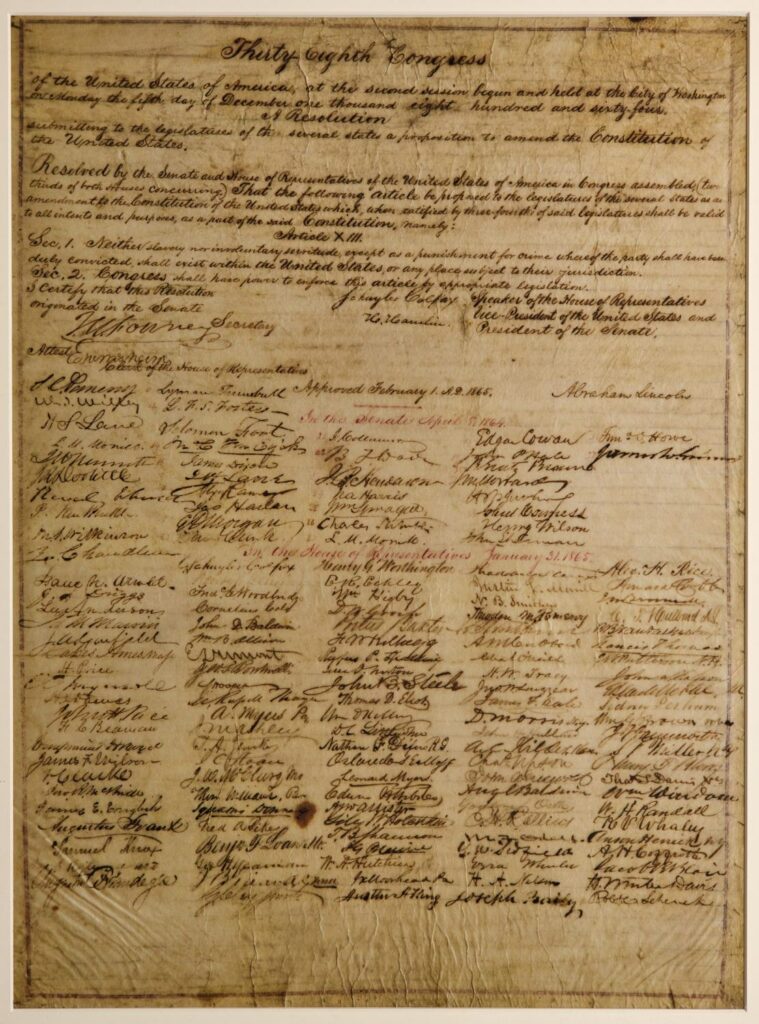

In 1865, the 13th Amendment to the Constitution permanently abolished slavery in the US. Unlike the Emancipation Proclamation, which applied only to the Confederate states, it freed enslaved African Americans across the nation.

As important as it was, the 13th Amendment left crucial questions unanswered. What was the legal status of America’s black population? What were their rights? They were free but would they be citizens?